Learnings

Challenges and opportunities for the creative and cultural sector on community financing: the Open Heritage Observatory Cases

Developed and carried out by Eutropian and Platoniq, the Open Heritage Training Programme was created with the aim to address urban professionals involved in issues related to heritage protection and adaptive reuse. Abandoned or underused sites pose a significant challenge to both the public and private sectors but also represent major opportunities. This is why we have developed training modules to help those interested in repurposing empty or underused buildings with symbolic or practical heritage significance.

Developed as part of the Open Heritage project and funded through the Horizon 2020 grant scheme of the EU, the OH Training builds on the expansive knowledge base of the project, generated since its launch in 2018, notably, capitalizing on the 16 Observatory Case studies that were developed in detail at earlier stages of the project.

The Observatory Cases look at how various (e.g. financial, governance, territorial) aspects of cultural heritage reuse come together to form successful initiatives in various European local contexts.

The Open Heritage Training on Adaptive Heritage Reuse was created first, in an online classroom setting hosted on Zoom and utilizing MIRO interactive boards. The training sessions were held on a bi-weekly basis, with the following five modules: (1) Heritage, (2) Governance, (3) Financial and (4) Territorial Impacts of aspects of adaptive heritage reuse. The final module brought (5) Integrate the above presented aspects into one comprehensive model. As a follow up to the online training modules. The Module 3 on Community Financing delves into the challenges to fund these projects, as we present below.

The study Reshaping the crowd’s engagement in culture shows that in the European cultural and creative sector alone, individuals and cultural organizations all over Europe have launched some 75,000 crowdfunding campaigns since 2013, collecting a total of €247 million, most particularly in the United Kingdom and France.

One of the most significant findings from European data is that only half of crowdfunding campaigns have been successful in meeting their target, though. Particularly striking is the fact that these €247 million collected in total represent only 7% of the total committed amount (which was €3.4 billion). That is, there is a ‘black hole’ of over €3 billion that eventually was not assigned to crowdfunding campaigns, as their minimum funding goals were not reached. Besides suggesting that unsuccessful campaigns are over-ambitious in their demands for monetary resources, this also demonstrates one of the most common rules of crowdfunding platforms: when projects fail to reach an established funding target within a given time, all donations received from participants are refunded at no extra cost or contribution.

Amidst this complex scenario of great potential but many resources not being able to reach the culture and creative sector, in OpenHeritage partners have mapped funding strategies and organized inclusive business models and crowdfunding, exploring diverse partnership arrangements, business and finance practices to promote and facilitate community reuse and engagement with heritage sites.

In the illustration below, we present the main challenges identified in the OpenHeritage project, as we discussed in the Module 3 on community finance in the context of adaptive heritage reuse and management. As we can see, unpredictable circumstances, changes and challenges in relations among stakeholders, the political scenario and the complexity related to distribution and management of funds are relevant issues to take into account.

OpenHeritage Policy brief #03: Financing the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage: Enabling complementary financing instruments for bottom-up initiatives.

To deal with these challenges, OpenHeritage partners found that funding diversity counterbalances the different interests of the stakeholders involved, contributes to sharing risks and responsibilities, strengthens connections between people and their surroundings and makes a project more resilient through economic cycles or in times of economic crisis. In this sense, “mosaic-type” funding models such as match-funding, which we discuss later in this post, have a high impact on the community while contributing to territorial integration.

Check below this interesting OpenHeritage Observatory Case for insights as to how to diversify funding mechanisms in a complex scenario, combining crowdfunding with other approaches:

LaFábrika detodalavida, Los Santos de Maimona

The initiative of LaFábrika detodalavida began at the end of 2009 with a small group interested in creating a project out of the abandoned cement factory space. The factory had suffered neglect and vandalism and was in a complete state of disrepair. The original idea was to draw a connection between public intervention and the restoration of the space, though with a focus on political, public art. The project is an opportunity to rewrite a history of industrial failure in a poor region of Spain

LaFábrika has chosen to organize itself horizontally, focusing governance on individual projects and work groups under a common mission. This governance is based on micro-agreements (microconvenios): a particular group of individuals or entities working on a specific project together (members, time, commitment and responsibility). Work groups also work on issues such as economic sustainability.

💰 Funding

LaFábrika detodalavida receives basic services and materials from the town council, but aside from these provisions, the project is entirely self-funded.

In 2013, the collective launched a crowdfunding campaign on the Goteo platform.

LaFábrika detodalavida has also received smaller amounts of money from grants and awards, but in general they have managed to accomplish impressive results with a very limited budget.

Delocalisation and Match-funding

Going back to European data, another significant finding in Reshaping the crowd’s engagement in culture is the relative ‘delocalisation’ of platforms. Although up to 600 crowdfunding platforms have been active at any given time in Europe, almost half the campaigns started by creators of European projects were hosted on US-based platforms, mainly Kickstarter and Indiegogo. These two platforms have a global reach and are, by a large margin, world leaders in hosting campaigns from different countries. In relation to these deficiencies and possibilities in the development of crowdfunding, in parallel with other methods such as equity crowdfunding3, in 2013, some platforms started pilot projects in match-funding. The method of match-funding allows money successfully obtained in a campaign to be increased with capital from an institution providing additional funds.

Since crowdfunding first appeared, and with the proliferation of platforms, various systems and formulas of operation have appeared within the general crowdfunding model. One such system, still in its early days, is match-funding (co-funding between citizens and institutions), which permits public and private organizations to double financial contributions for projects from individual users. After an analysis of the state of the art in match-funding practices, this paper focuses on a case study of the Goteo.org platform, a pioneer in the international development of this model.

Before crowdfunding, the concept of match-funding with matching donations or payment of funds was already in use in the contexts of charity, philanthropy or the public good4. For institutions, the most popular model was one whereby a public organization, sponsoring body or corporate social responsibility department completed funding in the form of investment (a subsidy or loan) in a project that had already obtained a substantial amount of its target funding from other sources5. The first crowdfunding platforms in Europe that tried different forms of match-funding in 2013 were Goteo in Spain, with the support of the International University of Andalusia (UNIA), and KissKissBankBank in France, with the support of La Poste, while in the US it was Indiegogo, with the support of the Kapor Foundation6.

There are numerous institutions interested in promoting and supporting creative projects in the field of culture, heritage, research, technology or science. Sometimes they find it difficult to make their contribution visible, to reach the right industry and audience, or to get communities involved. Institutions are also increasingly looking for more ways to help these projects raise funds, better manage high administration costs, and ensure long-term project sustainability. A matching financing program provides a powerful tool to accomplish all of the above.

In counterpart financing, an institution makes a sum available to develop a specific area (culture, education, etc.), then calls on the community to present projects in this area and calls on the general public to commit. with the money. The crowd supports a specific project by making small donations of funds that the institution matches with the same amount. For example, if the crowd donates €1,000 to a specific project, the matching funding institution (a public or private organization) will also provide €1,000, thus increasing the total project budget to €2,000.

Thus, match-funding programs are calls to promote projects or organizations through financial aid according to the criteria defined by the collaborating public and private institutions. On the one hand, the beneficiaries must go through a crowdfunding campaign, and on the other hand they participate in a training program to validate the interest of the public and the viability of the proposal. Based on the success of the campaign, financial aid from the collaboration agreement with the collaborating public or private entity is also added. For both public or private entities and organizations as well as individuals, match-funding allows funds to be distributed through a model that promotes “efficient excellence” thanks to citizen participation, agility, transparency and capacity-building.

As discussed in the report Matching the crowd: Combining crowdfunding and institutional funding to get great ideas off the ground, based on a pilot experience with different campaigns on crowdfunding platforms for the artistic and social sectors, the match-funding method could offer a number of advantages with regard to project funding, including:

- Helping provide additional funds for project campaigns

- Improving the chances of success for campaigns

In this publication, the advantages and impact of this method of crowdfunding compared to the traditional method is analyzed using data collected on the behavior in 24 match-funding calls for projects runned by the Goteo Platform, from 2013 to 2022. The results show that match-funding campaigns are more likely to be successful, significantly increase average donations and generate new dynamics of institutional cooperation and proximity in the support for initiatives. From this analysis, we see that civic match-funding can become a powerful instrument for public participation and policy innovation, with many initiatives crossing boundaries between activism, advocacy, social entrepreneurship and social innovation. In this sense, from the mechanism of match-funding, in which funds are boosted by combining citizen and public institution commitment, we can envision new forms of participation and democratic innovation. The novel concept of “crowdvocacy”, for instance, could emerge as a distributed but coordinated process among different actors and platforms where civic initiatives increase their influence in public life, from citizens’ awareness and engagement to empowerment, and wider participation in democratic life.

Check below this interesting Future Heritage Lab case for insights from a successful match-funding campaign:

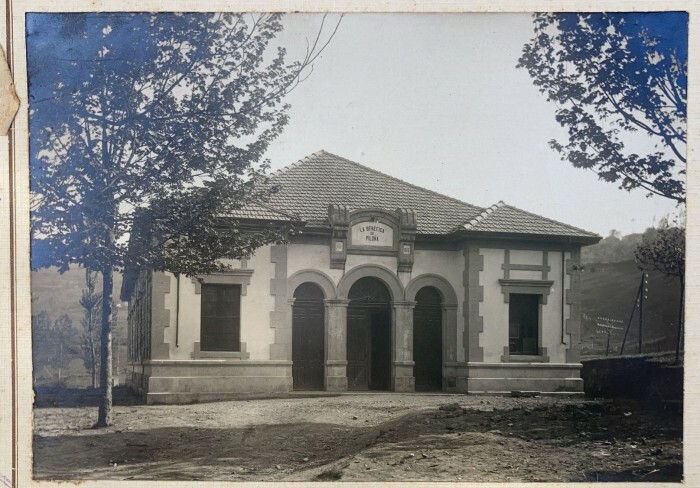

La Benéfica, Piloña

The space to be rehabilitated was founded by the La Benéfica de Piloña (Citizens’ Association). The purpose of this association was that the neighbors (18,000 at the time) helped each other in moments of illness, widowhood, etc. With the contributions of the members they attended to needs that the State or other institutions did not cover. In 1926 they built a building of about 400 m² that served as a theater, dance hall, social meeting place and cinema every Sunday. The project ended in 1946. The warehouse became a candy factory, then a parking lot and was finally abandoned. Now, the goal is to rebuild the space so soon all the neighbors can co-create through arts and culture.

💰 Funding

The funding sources include public grants and funds and private capital from the members of the association. La Benéfica also has the support of the City Council of Piloña, local companies such as Ordum Cervezas Artesanas, Sidra Viuda de Angelón or Asturcilla, and also national companies such as the Spanish streaming platform Filmin. Its crowdfunding campaign raised € 136.425 and was matched by a private matcher with 20,000, namely the Primavera Sound Festival, a music festival that takes place in Barcelona.

In conclusion, there are many challenges the creative and cultural sector faces when it comes to community financing, as we presented in the OpenHeritage Module 3, from a gap to access potential crowdfunding donations and promoting more successful campaigns, to changing political and economic environments, hurdles related to multi-stakeholder governance and unequal distribution of funding. Nonetheless, we have explored as well the advantages of diversifying funding strategies and exploring match-funding and Crowdvocacy as pathways to engage communities, private partners and public institutions, offering possibilities to innovate in crowdfunding campaigns.

Resources

OpenHeritage Materials:

OpenHeritage Observatory Cases

The civic crowdfunding homework handbook: https://www.dropbox.com/s/z76a3pbm2ab6ucf/Goteo-playbook-A3-ENG.pdf?dl=0

The project template: https://www.dropbox.com/s/z2jrzfgp3xq4xvp/Goteo-playbook-A3-ENG-Central-A4-ENG.pdf?dl=0

For some resources on crowdfunding and community funding, please check out:

European Commission proposal on crowdfunding:

Crowdfunding I European Commission

Charbit, Desmoulins, Civic Crowdfunding: a Collective Option for Local Public Goods?

Crowdfunding for local regeneration:

Catalonia Coop/SSE + Covid-19, a Cooperative Contingency fund to support initiatives that are coordinating a response to the Social and Health Emergency coordinated by Platoniq/Goteo: https://en.goteo.org/project/fons-cooperatiu-front-l-emergencia-social-i-sanita

For our report lovers:

http://crowdfunding4culture.eu/platforms-map

For resources on Match-funding, please check out:

Besides pooling resources, crowdfunding is also is a way to work on “Crowdvocacy”, a term coined by Platoniq; read this for how active citizen participation on funding projects could represent a more fair means to create policy: https://medium.com/@platoniq/crowdvocacy-amplifying-democracy-by-bridging-political-participation-digital-campaigning-a364a2cfd6db

This link is for a specific Matchfunding experience runned by Goteo/Platoniq with a Barcelona municipality to support the social enterpreneurs ecosystem and the commons in the city: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/matchfunding-social-entrepreneurship-and-the-commons-collaborative-economy-in-barcelona/2018/03/09

This resource is for comparative results of success rates on crowdfunding vs matchfunding. It is also quite relevant as this paper also looks at Goteo’s data. By Enric Senabre and Mayo Fuster Morell from The Dimmons Research Group (IN3-UOC): :https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326645598_Match-Funding_as_a_Formula_for_Crowdfunding_A_Case_Study_on_the_Goteoorg_Platform

Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces. Edited by Daniela Patti & Levente Polyák (EUTROPIAN)

https://cooperativecity.org/product/funding-the-cooperative-city/

Please note that this publication is worthy of a close read because it covers different funding schemes that go beyond crowdfunding. It features Goteo, LaFabrika detodolavida, Platoniq’s OpenHeritage Observatory Case, and the Trias Foundation.

Regulations and accountability:

A more complicated issue is the part of the relevance on crowdfunding financial tools regulations: https://eurocrowd.org/2019/12/19/agreed-harmonised-eu-rules-to-boost-european-crowdfunding-platforms/

Building in accountability:

Relevant literature on the match-funding + civic crowdfunding marriage:

- Triggering Participation:A Collection of Civic Crowdfunding and Match-funding Experiences in the EU including Goteo’s case

- Ezrah Bakker and Frank Jan de Graaf, Civic crowd-funding: not just a game for the self-reliant;

- Davies, Civic Crowdfunding: Participatory Communities, Entrepreneurs and the Political Economy of Place;