Deep dives

Recovering Collaborative Governance of architectural assets through Design Justice

Imagine a former industrial site now abandoned, that local residents want to convert into a community school!

Imagine a park that is used on a daily basis by local young people, local organic farmers and by a collective of elderly people. Imagine that these residents could participate in taking decisions about the future of the area!

Imagine a neighborhood once derelict and now upcoming, at risk of aggressive gentrification but with the presence of a strong grassroots community and local commerce interested in being involved in changing the future of their area for the best!

In the OpenHeritage EU project, partners explored how such participatory processes can be applied to heritage. OpenHeritage identifies and tests the best practices of adaptive heritage re-use in Europe, including models of governance.

Developed and carried out by Eutropian and Platoniq, the Open Heritage Training Programme was created with the aim to address urban professionals involved in issues related to heritage protection and adaptive reuse. Abandoned or underused sites pose a significant challenge to both the public and private sectors but also represent major opportunities. This is why we have developed training modules to help those interested in repurposing empty or underused buildings with symbolic or practical heritage significance.

Developed as part of the Open Heritage project and funded through the Horizon 2020 grant scheme of the EU, the OH Training builds on the expansive knowledge base of the project, generated since its launch in 2018, notably, capitalizing on the 16 Observatory Case studies that were developed in detail at earlier stages of the project.

The Observatory Cases look at how various (e.g. financial, governance, territorial) aspects of cultural heritage reuse come together to form successful initiatives in various European local contexts.

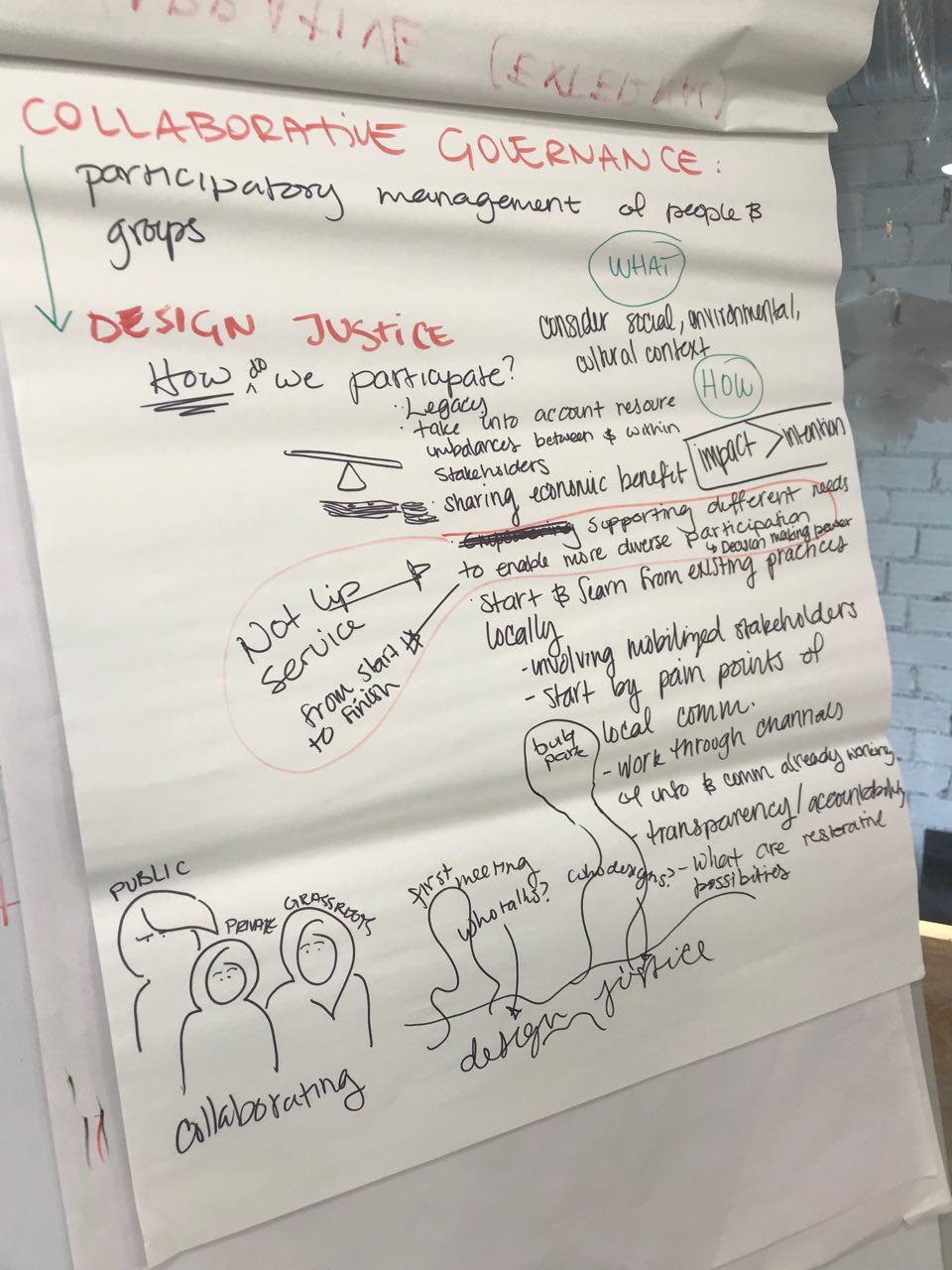

The Open Heritage Training on Adaptive Heritage Reuse was created first, in an online classroom setting hosted on Zoom and utilizing MIRO interactive boards. The training sessions were held on a bi-weekly basis, with the following five modules: (1) Heritage, (2) Governance, (3) Financial and (4) Territorial Impacts of aspects of adaptive heritage reuse. The final module brought (5) Integrate the above presented aspects into one comprehensive model. As a follow up to the online training modules. The Module 2 on Governance is dedicated to exploring collaborative governance in depth, as we discuss in this post.

More specifically, OpenHeritage unpacks collaborative governance models. Among principles and approaches useful for such a perspective, Design Justice gives collaborative governance a meaning and orientation that allows it to become a method and tool for diverse and inclusive participation that aims for greater social justice.

Why do we think this question is relevant and related to our ethical compass (The story of me)

In OpenHeritage (OH), partners worked on collaborative governance of the online community and platform of the project, which aims to develop and share best practices concerning adaptive heritage reuse. Within the OH platform participants and administrators can co-create, exchange ideas, and collaborate to construct participatory spaces and projects within the larger OH initiative with 16 partners involved from Italy, Hungary, Poland, Belgium, U.K., Germany, Spain and Portugal as well as with the OH labs in Rome, Budapest, Sunderland, Prädikow, Warsaw, and Lisbon. The labs are heritage sites that use the platform as a tool and space to manage, and conduct their work with their communities and stakeholders.

However, a platform and its governance are not inherently oriented toward the desire for greater good without people and ideas to make it so.** Design Justice within this context serves as a framework to build ideas and practices that give importance to vulnerable communities and individuals** that might be involved and consciously pushing the needle of the project’s ethical compass.

State of the art

What is Collaborative Governance?

Collaborative governance now for almost the last four decades has offered up the opportunity for new and refreshing ways to rethink how we make public spaces and services possible. Broadly described, collaborative governance is a process in which ‘state and non-state actors jointly address an issue be they civil society, public, private organizations or individual citizens’. However, this broad definition without an ethical moral compass does not inherently promise a means for a stronger democratic process or greater social transformation for a more egalitarian society.

Within OpenHeritage we are collaborating with multiple organizations, communities, and public entities, in different cities around Europe involved in adaptive reuse of heritage sites, working to support a more participatory process. For us, collaborative governance is not a hollow term meant to pay lip service to participatory processes. So we want to reclaim collaborative governance as a means not just for rethinking public services and goods, but also making them more transparent and fair.

The Critique

The term collaborative governance is incredibly flexible, and it does not explicitly define who the non-state participants are or what should be the priorities within a collaboration.

And one strong, academic critique has been that collaborative governance is actually ‘post-political’. The term post-political came about a few decades ago where rather than see real change that incorporates disensus and different political opinions, public spaces and goods were managed through the ‘expert social administration’. In regards to urban governance, the post-political attribute refers to a process of acting in the best interest of a city without further clarity as to who defines for whom and how we better the city and thus opens up the possibility of reinforcing pre-existing power dynamics and inequality.

Incorporating the post-political concept, we want to question the underlying ideas behind collaboration and consensus. When implementing collaborative governance is there space for acknowledging disensus and power dynamics? Within the lens of post-political it’s important to acknowledge that we cannot assume that inclusion and diversity are a given within consensus-oriented governance. That being said, this lens of a post-political approach helps us push towards our desire towards a collaborative governance that addresses power inequality and creates processes and references not just for ourselves but those doing similar work as well.

Incorporating Design Justice

To recover collaborative governance as an important pillar for building more socially just societies that designate greater decision making power to those traditionally marginalized, we can give it a backbone with the principles of Design Justice.

Design justice came about during an Allied Media Conference in 2015. Since then as an organization Design Justice has come forth with an explicit political agenda for a practice that ‘center[s] those who stand to be most adversely impacted by…’ a project or process. This idea goes against the traditional paradigm of design which generally looks like when an expert such as an architect or urban designer creates from their singular vantage point and with great decision-making power, designs the material spaces we live in. Consider the works of Oscar Niemeyer, a famous architect whose designs shaped the landscape of Brasilia, the capital of Brazil. From an aerial perspective his buildings and lines have a graceful or even feminine flow, but on the ground it’s an un-walkable city where if you don’t have a car you don’t get far. However, within the practice of design justice, designers facilitate the design process to be more oriented around impacted communities rather than be keepers of a singular solution for many. Platoniq and OpenHeritage partners, in the context of the project, have mapped, analyzed and facilitated participation and the management of public spaces and commons. In doing so, we fomented including rather than alienating residents and communities from places.

Infusing collaborative governance with Design Justice creates radical new possibilities for design and collaboration.

For example, let’s take a look at Ansell and Gash’s (2008) more nuanced six principles of collaborative governance (participedia):

- the process is initiated by a public agency or institution

- includes participation of non-state actors

- participants are not only to be consulted - they have decision making power

- the forum is a formal process and organised formally

- decision making is consensus-oriented

- the focus is related to public policy or public management

It looks like it could lend itself to better governance, but again who are these participants with decision making power? And how are they developing a consensus?

Now let’s look at those principles through the lens of design justice:

- the process is initiated by a public agency or institution

- includes participation of non-state actors centralizing people who are normally marginalized

- participants are not only to be consulted - they have decision making power to open up the design process to those who will be most impacted by its outcomes

- the forum is a formal process and organised formally and is transparent and accessible

- decision making is consensus oriented to dismantle structures that marginalize, dehumanize, subjugate, and oppress others while centralizing voices that are most marginalized by institutional racism, patriarchy, and colonization

- the focus is related to public policy or public management

What makes us excited about Design Justice is that it gives us an ethical compass for deciding who gets to sit at the table and how we should orient ourselves in creating new systems and infrastructure for communities.

Story of us (a series of objective data to back up the idea)

Much of how the Design Justice principles are interpreted in OH happen through developing new features and adapting the online platform of the project, Decidim.

Creating a Case with and for Sortition

Sortition very basically described is when participants in a project, community, or space are randomly selected into a working group. The idea is that through random selection the working group is not defined by politics or bias that might be held within the group. To create example of how this might work within OH, Platoniq initiated the creating of a collaborative, participatory text, ‘OpenHeritage Manifesto’. The text draws from each word in the title of the project ‘OpenHeritage: Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Reuse through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment’ and partners selected at random write an entry that connects their individual values to OH to create a whole text that reflects a unified vision from different heritage contexts. The text itself demonstrates how the practice of sortition has worked within the OH initiative and also serves a reference in terms of process for partners and those within the larger heritage community looking for practices that take an unbiased look at their own diversity to collaborate and co-create.

Developing a Feature to Measure Volunteer Hours

Working with the lab from Sunderland, Platoniq developed a feature for Decidim that allows volunteers to track their hours. The effort is a means to demonstrate the manpower often precarious that goes into getting some heritage projects off the ground. Similarly, the lab in Prädikow has also become interested in getting involved, to potentially demonstrate to public administrators the amount of unpaid labor that happens to push for more compensation for work at their heritage site. What was inevitable in both projects was the fact that volunteer labor would happen and was necessary. However, to create heritage practices that visibilise the work and even precarity might serve as a tool to create better working conditions or generate data to further build on the case for wider public support for what eventually become public goods i.e. sites of adaptive heritage reuse.

Working with Residents to Develop a Feature to Manage Collective resources

In the lab in Rome, residents of Centocelle have formed a cooperative, CooperACTiva. The cooperative intends to give bike tours of the neighborhood, which was a former stronghold against fascism. Using the Decidim platform they intend to create a system for reservations and bike rentals. The initiative is completely resident led and working them allows for Platoniq to adapt the platform to their needs rather than having an imposed platform structure within their organising.

Call to action

Do you have any example of justice in Design especially in terms of participation and technology? If we’d love to hear more!

References

- Design Justice Network

- Participedia

- Wikipedia & Davidson, M., & Iveson, K. (2015). Recovering the politics of the city: From the ‘post-political city’ to a ‘method of equality’ for critical urban geography. Progress in human geography, 39(5), 543-559.

- Hutswit, Gary (director). (October 2011). Urbanized [documentary]. United States: Swiss Dots

- OH Training - Module 2 Governance