We currently live in a reality where computers and algorithms decide which patients are on a list for priority surgery in a public hospital, flag fraud amongst people collecting public benefits or welfare and determine the severity of a domestic violence incident. These services are developed and implemented through our governments with little or no transparency about how, when, or why computers and algorithms are making these decisions.

Building off of the work of the AI procurement primer by NYU, Platoniq and Civio facilitated a workshop to try to start asking how we might create more transparent processes for AI procurement and design, using frameworks for participation and governance such as Decidim.

Approaching procurement and design often takes place through a closed technical or legal process. The workshop aimed to start a conversation and begin developing ideas on how to open up public AI governance and support safety, transparency, and public participation for the services and tools that affect regular peoples’ everyday lives.

Nadia Nadesan during the workshop

Decidim Fest, 2023

In the past decade, we have seen an increase in the initiatives related to the growth and development of AI, and so has government design and acquisition of AI systems. In Barcelona, some examples of AI in the city are:

- AI Beach Monitoring Capacity

- AI Classification of Citizen Inquiries

- AI in Social Services

While these examples are cited publicly, research by civil society organizations highlighted even more cases that use social scoring such as Viogen, Bosco, or RiisCanvi.

A Need for Criticality in Public AI Design and Procurement

The great truism that underlies the civic technology movement of the last several years is that governments face difficulty implementing technology, and they generally manage IT assets and projects very poorly.

The development, design or procurement of goods and services by the government is nothing new. However, using algorithms in public services and goods needs a more critical approach. Coded bias and error in decision-making when using AI for public services have appeared in multiple cases across Europe over the last five years. Over the past decade, notable cases of oversight and AI in public service have severely impacted vulnerable communities.

Dutch Childcare Benefit Scandal

In 2013 the Dutch government deployed an AI decision-making system to detect fraud by applicants receiving childcare benefits. This system utilized algorithms to assess the likelihood of inaccuracies in applications and renewals, to identify potential fraud. Individuals flagged by this system had their benefits temporarily suspended pending investigation. To demonstrate the effectiveness of their fraud detection methods, tax authorities aimed to recover sufficient funds from suspected fraudsters to cover operational costs. Despite efforts to clarify discrepancies or missing information, those accused of fraud often faced immense obstacles as tax authorities declined to provide explanations for their decisions. One reason was that the AI decision-making system used unsupervised learning to create risk assessments. This is often referred to as a ‘black box’, where there are inputs or information about those receiving benefits put in and then the AI would deliver outputs; however, it remains either opaque or not easily understandable how the provided result is obtained. So, there was no transparent logic or evidence that explained why the AI identified and labelled certain people as fraudsters. In real-world terms, this meant that caregivers, journalists, local politicians and civil society at large found it difficult to engage with such a system and demand an explanation or accountability when the system was wrong.

Often the case was that applicants (i.e. caregivers, guardians, and parents) made small errors, such as missing a signature or a late payment. These mistakes would result in the painful consequence of repaying large lump sums of money and being labelled as fraudsters. The repayment and labelling amplified the hardships facing these families – including debt, eviction, and even unemployment – which then put stress on their mental health and personal relationships.

Tens of thousands of families were affected by false accusations. The Dutch childcare benefits controversy emerged in 2018 and remains a significant political issue in the Netherlands today. This scandal ultimately resulted in the resignation of the Dutch Cabinet in 2021.

Scoring the Unemployed in Austria

The Austrian employment agency, known as AMS (Arbeitsmarktservice), is a government body responsible for assisting job seekers. In 2016, AMS initiated a program to assess a person’s employment prospects within the labour market.

Three years later with the support of an external contractor, Synthesis Forschung, at a cost of €240,000, AMS announced the adoption of an automated scoring system for job seekers. This system assigns a score to each individual based on various attributes, categorizing them into three groups: Group A for those deemed to require no assistance in finding employment, Group B for individuals who may benefit from retraining, and Group C for those considered unemployable, receiving reduced assistance and potential referral to other institutions.

AMS asserted that the algorithm enhanced efficiency by directing resources toward individuals most likely to benefit from support. However, concerns were raised about the potential discrimination inherent in the algorithm’s decision-making process. Snippets of the code that were made public revealed that certain demographic factors such as gender, disability status, and age, are weighted negatively, disproportionately affecting women, disabled individuals, and those over 30.

The consultation that would produce a person’s employability score would often last less than 10 minutes. In most cases where a score was given, there was a lack of transparent and legal regulation often reflected in the fact that there was no space to file a complaint or contest their employability score.

From January 1, 2021, the Austrian data protection authority prohibited the use of the system. The decision was made based on the fact that the AI system failed to meet the requirements of GDPR. Additionally, the scoring of an individual’s ability to gain employment based on certain identity markers was classified as profiling for which there needs to be legal authorization which was not met by the AMS in processing of personal data.

Creating and contracting external AI services and goods is often treated with the same attitude as any other technology. However, considering the impact of AI from the Netherlands to Austria it seems that governance around AI requires more accountability and pathways to recourse. For the past decade, governments have yet to implement systematic communication around the development or use of AI systems in the public sector.

The Use of AI in Spain’s Public Services

Viogen

In 2004, Congress in Europe passed legislation aimed at combating gender violence, heralding the introduction of VioGén. This system makes predictions based on risk factors to evaluate the level of threat faced by victims of gender-based violence. By analyzing 37 risk indicators, encompassing both aggressor traits and victim vulnerability, VioGén categorizes risk into five levels: not noticeable, low, medium, high, and extreme.

Risk assessment tools are designed to categorize gender violence cases according to the level of risk that can be foreseen. Therefore, they aim to provide an accurate prediction of which victims of gender violence are more likely to be assaulted again and therefore need protection. A risk score, in this context, does not evaluate the gravity of the past or current incidents but rather predicts the likelihood of having a future episode of gender violence -what is assessed is the risk of recidivism of the perpetrator. Since its inception, VioGén has assessed over 700,000 cases of gender-based violence in Spain as of October 2022. However, important to know is that there is no independent audit or analysis of the service that takes a critical look at how it has improved or worsened access to justice for victims of gender-based violence.

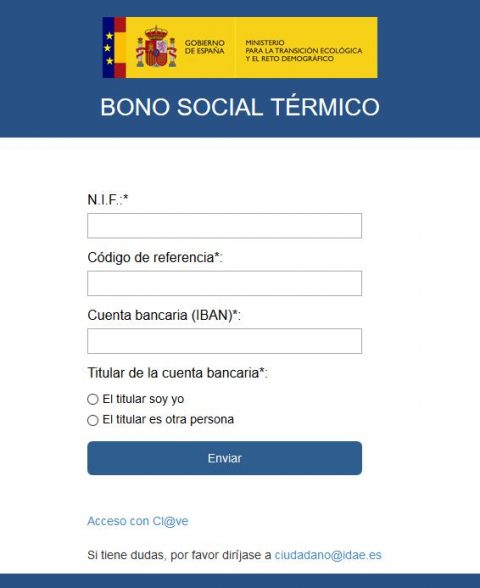

Bosco

The recent surge in electricity prices has exacerbated energy poverty, affecting 16% of households in Catalonia in 2021. To mitigate the effects of this crisis, social support measures such as the electricity discount scheme implemented by the Spanish Government have been instrumental in assisting affected families. However, concerns have been raised regarding the allocation process following changes in eligibility criteria and the introduction of the BOSCO software in 2017. To increase transparency and ensure accountability, the Civio Foundation developed a BOSCO simulator in 2018 to assess the system’s functionality. Yet, the results generated by the simulator raised questions about the effectiveness and fairness of the allocation process. In adherence to the Transparency Act, Civio sought access to information regarding BOSCO, including its source code, to gain deeper insights into its operations. While the Spanish Government provided technical specifications and test data, it withheld access to the software source code (now at the Supreme Court), raising further concerns about the transparency and accountability of the allocation process.

It should also be noted that in the case of the support scheme, the application was entirely developed by the Ministry of Ecological Transition and not by a third party.

RisCanvi

RisCanvi is an AI system developed to calculate the risk of future violent behaviour of incarcerated individuals. It was originally developed for violent offenders charged with death or serious bodily injury. However, it has since been expanded and RisCanvi is used to identify if a person is low or high risk for reoffending which then informs how their case is treated by the state.

Within Catalan prisons and throughout Spain, inmates are monitored and evaluated by the Treatment board which includes social workers, lawyers, psychologists, etc. that review an incarcerated person’s progress. Before RisCanvi the assessment of whether a person would reoffend was made with clinicians. Now, the Treatment Board’s observations are aggregated into a checklist of 43 risk factors taking into account gender, age, presentation of antisocial behaviour, length of their sentence, mental health, family visits, history of family relationships, engagement in leisure activities etc. These risk factors are then analyzed with RisCanvi which then predicts if an incarcerated person will reoffend. A study by Bikolabs shows that 9 out of 10 officials affirm the decision made by RisCanvi. However, is this a sign of the system’s success or a cause of concern? A recent study concludes that RisCanvi can detect 8 out of 10 prisoners who re-offend, however, 2 are false negatives. Moreover, when looking at the capacity of Riscanvi to identify those who will not re-offend, it showed that 4 out of 10 times non-repeat offenders are incorrectly identified as high risk.

So, what defines whether this system is successful? Is it the trust of the officials who use it? Is it its widespread implementation? Or how does it measure up in terms of accuracy and specificity? Part of creating more participatory governance in AI is to collectively define what makes a public service or good successful. Is it possible to incorporate the voices of those most affected by AI in its design and implementation?

AI Governance

One critical aspect of AI governance around the world lies in the current lack of common structures or practices to allow for greater transparency and accountability surrounding decision-making processes. While AI systems are increasingly being integrated into public services, there is often little clarity on how those who are affected are able to contest and seek recourse when the systems propagate discriminatory biases, generate errors, or malfunction. Moreover, the absence of accountability measures means that errors or biases in AI systems may go unchecked, perpetuating inequalities and undermining public trust. As such, there is a need for robust governance frameworks that prioritize transparency, accountability, and spaces for civil society and affected communities to meaningfully influence the direction of services that implement AI. Without safeguards in place, the adoption of AI in public services risks exacerbating existing social disparities and eroding public confidence in government institutions.

the absence of accountability measures means that errors or biases in AI systems may go unchecked, perpetuating inequalities and undermining public trust.

AI Governance in Spain

One avenue for enhancing AI governance is the establishment of independent regulatory bodies, akin to the Spanish Agency for the Supervision of Artificial Intelligence (AESIA). Modelled after entities such as the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) and the National Commission for Markets and Competition (CNMC), AESIA would operate autonomously from other public authorities, thereby ensuring impartial oversight of AI applications in the public sector.

Additionally, municipal strategies, like the one implemented in Barcelona, underscore the importance of multi-stakeholder involvement in AI governance. By establishing cross-departmental committees within local councils, municipalities can ensure that AI-based solutions undergo comprehensive scrutiny and approval processes. Furthermore, the inclusion of AI councils composed of researchers, academics, and members of civil society promotes diverse perspectives and ensures that ethical considerations remain at the forefront of decision-making.

Civil Society and AI Governance in Europe

In Europe, specific initiatives such as AI registers exist to make the types of AI services and tools being implemented in the city more visible. For example, Barcelona is part of the Cities for Digital Rights initiative and has planned to create an AI register, a commission for promoting ethical AI in Barcelona City Council, an advisory council of experts in AI, and launch a citizen-participation body. However, there is often a lack of oversight in which automated decision-making systems are used to cite the city’s use of AI and which are left to civil society to investigate.

Conclusion

As AI systems become increasingly integrated into public services, there is a critical need for transparent and accountable governance. Recent cases, such as the Dutch childcare benefits scandal and Austria’s employment scoring system, highlight the potential harm when AI systems lack oversight and transparency. These systems often operate as “black boxes,” leaving affected individuals without recourse to challenge errors or biases. As public services rely more on AI, it is essential to implement robust governance frameworks that include civil society participation, independent audits, and clear pathways for accountability to prevent the perpetuation of inequalities and restore public trust in government institutions.

The workshop, facilitated by Platoniq and Civio, focused on exploring ways to create more transparent AI procurement and design processes by leveraging frameworks like Decidim, a platform designed for participatory governance.

The goal of the workshop was to plant the seeds for what raising awareness and participatory AI governance could look like in practice. It encouraged open discussion among experts, residents, civil society, and interested individuals to advocate for a more democratic governance model where citizens, researchers, and civil society collaborate to shape how AI tools are designed and used in public services. Ultimately, working within the Decidim community allowed us to exercise the notion of creating open and accessible avenues for public engagement in AI governance, moving away from the closed, technical processes that currently dominate AI implementation in governments.

Note:

The workshop, facilitated by Platoniq and Civio, took place at Decidim Fest 2023. Participation in Decidim Fest played a crucial role in initiating conversations about transparency and accountability in AI governance.