Ernesto Ganuza is a researcher and is passionate about organising deliberative spaces. He spends his time promoting deliberation, structuring it, and organising it in order to study how these processes offer people the possibility to speak, express their opinions and make decisions in the current political context, as well as how they contribute to redistributing power and strengthening citizen organisation.

C. Given your experience designing and carrying out participatory processes, is there any participatory process in Spain that has particularly caught your attention?

E: I find all the processes I have created fascinating, each one is unique because it depends on factors such as participants, funders and available resources. A deliberative process always generates a special energy because you create a group that discusses a very specific topic for a long time. This raises a lot of barriers and, in the end, people become empowered.

A deliberative process always generates a special energy because you create a group that discusses a very specific topic for a long time. This raises a lot of barriers and, in the end, people become empowered.

My first big process was in 2008, in Andalusia, on water. It brought together 150 people from different parts of the region, who discussed public policies related to water.

C: Talking about the participants, in a deliberative process people are usually selected by lottery, do you think this is a good way to achieve representativeness?

E: Yes, the standard academic process includes the use of lottery, selecting people randomly to invite them to participate in the deliberative process. This sample can be adjusted according to sociological profiles, depending on the topic, and variables such as age, gender and attitudes can be included. Sometimes certain groups are prioritised, as in the case of an issue that affects more than one part of the population, but in general the idea is to ensure that diverse perspectives are represented.

C: So you advocate a ‘pure’ lottery?

E: Yes, because the lottery brings together people with very different life perspectives. This is the core value of lottery-based deliberation: it creates unique cognitive and relational dynamics. It is a way of generating genuine debate, where people do not know each other and are not influenced by prior interests. It is not magic, but a scientific process. Studies show that in these deliberative spaces, people are more respectful and empathetic, which facilitates the creation of a more enriching debate.

C: How do you get people from such diverse backgrounds to understand each other and collaborate in a deliberative process?

E: The essential thing is to ensure a horizontal and egalitarian space. When people don’t know each other and are discussing a specific topic, the dynamics change. It doesn’t matter if they come from different economic backgrounds; the crucial thing is that, in a deliberative space, everyone has the same right to participate and be heard. This facilitates the crossing of perspectives and allows the debate to be enriched. The key is that the process is not just about exchanging opinions, but about generating mutual understanding.

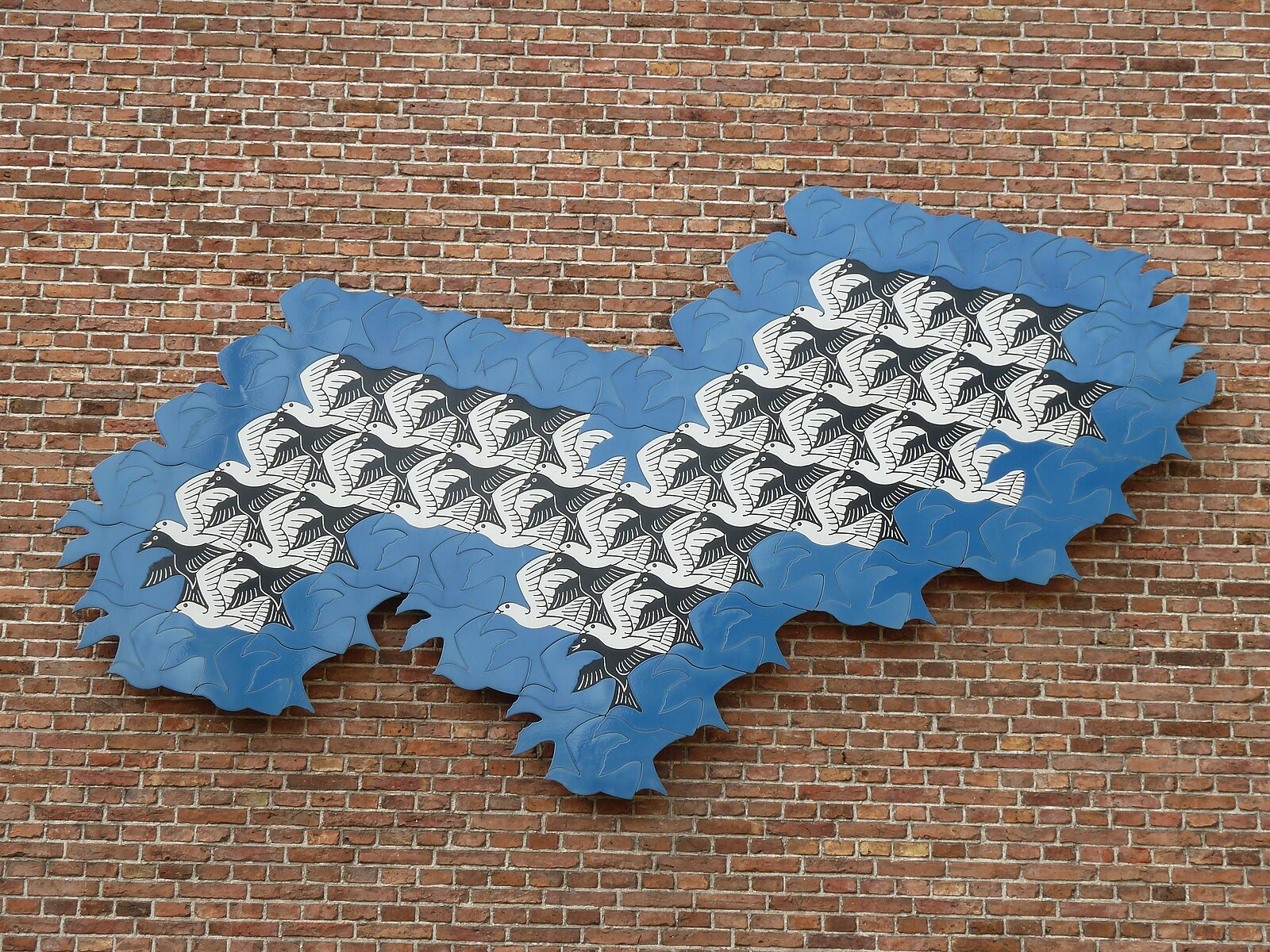

Wall tableau of a tessellation by local resident M. C. Escher on the Princessehof ceramic museum, Leeuwarden.

Bouwe Brouwer, 2011

C: How do you define the process of information transmission within these deliberative spaces?

E: The process is fairly standardised: a group of people is selected by lottery, then experts are invited to provide information on the topic in question. The participants, after receiving this information, debate to come up with recommendations on the public policies they are dealing with. This type of process, called a ‘mini-public’, seeks to ensure that participants are fully informed so that they can make informed decisions.

C: And what have you discovered in your research about how people process and use the information they receive?

E: One of the most interesting discoveries is that, contrary to the traditional view of information processing, the brain does not simply absorb data in a linear fashion. The transmission of information in these processes does not work as previously thought, as people not only process information internally, but also interpret it in a social context. In many cases, we justify our decisions a posteriori, and the social environment plays a key role in how we process information. For example, in many cases, people who quit smoking do so because they know someone who has quit.

C: How does this fit into the deliberative process?

E: The transmission of information in deliberative processes is much more complex. People learn in a meaningful way, but they learn in an active way, interacting with information and with other people. Learning is not limited to processing data, but involves a social and collective construction of knowledge, where interaction and diverse perspectives are fundamental.

Learning is not limited to processing data, but involves a social and collective construction of knowledge, where interaction and diverse perspectives are fundamental.

With the information we gave about the topics to be discussed, it happened that, at the beginning, no one knew how to proceed; many people failed, but at the end of the deliberation, almost everyone got it right, because it was a simple process. However, six months later, we asked them again and, although some remembered, not all of them did. Why does this happen?

Of course, the more traditional view would say that the person is incapable of learning, that they have cognitive biases that prevent them from processing information properly. In science it’s called Bayesian information processing. And this is where one of the big obstacles arises in the participation of people like us, normal people. It is said that people ‘don’t know’, that they are ‘not ready’ to make decisions on public issues, and that it is better to leave that to those who know, to the experts.

C: So, is it a question of capacity or attitude?

E: Exactly. In the behavioural sciences, it is shown that cognitive biases are not exclusive to those who do not know, but also affect experts, and to an even greater extent. Experts are so familiar with a topic that they become entrenched in their ideas, unwilling to consider new information. The point here is that biases are pervasive. We cannot think that it is only those who ‘don’t know’ who fall into them. Accepting biases is fundamental to understanding how the deliberative process works.

C: How do you make deliberation capable of overcoming these biases?

E: Deliberation allows stereotypes and biases to be tested. Through debate, people can move beyond these prejudices. It is not about turning people into experts, but about offering them a space where they can reflect calmly, just as experts do in their professional environment. This process allows them to question, modify and enrich their proposals, leading to more sophisticated results.

C: Could you explain how this process of critique and proposal works in participatory methodologies?

E: Sure. A common exercise is to ask participants to first make their own proposals. These proposals are then critiqued by other groups, who are free to do so openly. Criticism helps people to dig deeper into their proposals and modify them for the better. Through this process, what starts as a simple proposal becomes something much more elaborate and valuable. It is not about some people being smarter than others, but about using what we know about how we process information and how we are influenced by biases to improve collective decisions.

Calle Conde de Romanones 14, Madrid

Álvaro Ibáñez, 2014

C: Criticism doesn’t seem like a negative thing in this context?

E: Exactly. Criticism becomes a valuable tool for improving proposals. Instead of seeing criticism as an obstacle, it is seen as a support that helps to refine ideas and make them more robust. It is a process of collective growth.

C: And what other elements do you think are essential in participatory processes, beyond criticism and proposals?

E: One of the most important aspects is how information is presented. In a participatory process, you can’t just give information in a technical way at the beginning, because that creates alienation. People will feel lost if they don’t have a frame of reference. What should be done is to first provide a space for participants to discuss among themselves, reflect on their own views and come to conclusions before receiving information from the experts. In this way, when the experts intervene, participants already have a context from which to understand and question the information.

C: How does this influence the way we understand citizen participation?

E: Citizen participation has a transformative power. People start to feel ownership of problems and decisions, and that, for me, is the real value of participation. It is not just a technical process, it is a political issue, a redistribution of power. When people feel that they have a say in the decisions that affect their lives, they are truly empowered, although I don’t like that word very much. This transformative power is key to making our societies more democratic.

C: What differences do you find between an activist citizen movement and a deliberative process?

E: A citizens’ movement seeks to claim and mobilise within the political system, whereas deliberation does not have that aim. What deliberation seeks to do is to open up spaces for public debate, which are not necessarily made up of militant people.

What deliberation seeks to do is to open up spaces for public debate, which are not necessarily made up of militant people.

These people may have their own ideologies, but they are not there representing any organisation. The aim is to generate cross-agreements between different perspectives, rather than seeking unanimous consensus on specific public policy issues.

C: Why do you think design and advice are important in participatory processes?

E: Design is crucial because it conditions the space for exchange between people. Depending on how the processes are structured, some dynamics will be fostered or others. In terms of counselling, it is important at the beginning, until people become familiar with the process. It is not about perpetuating counselling, but about giving people tools so that, over time, they can manage the processes themselves. Counselling should be seen as temporary, initial support.

C: In short, what is the key to effective participatory processes?

E: The key is to create a space for exchange where people can reflect, propose, criticise and enrich ideas. From there, information flows more effectively, and the decisions that are taken are more complete and representative. Participation is not only a right, it is a collective process of learning and empowerment that can transform our society.

This interview took place at the Forum on Deliberation, Creativity and Democracy, organised by Platoniq, together with Deliberativa and FIDE, on 15-18 October 2024 in Barcelona. The Forum was supported by the Diputació de Barcelona and the Open Society Foundations.