Interviews

Amber Huff Commons in Focus: Amplifying Nature's Stories through Visual Cultures

A few weeks back, I had a fascinating conversation with Amber Huff, a researcher at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex and the coordinator of the Center for Future Natures.

Amber shared some thought-provoking insights on how visual cultures, such as comics and documentaries, can foster empathy and understanding, particularly around polarized issues. We also delved into the future of citizen assemblies and participatory policymaking, exploring the transformative potential of creative methods like fanzines and visual storytelling.

We also discussed the intriguing prospect of integrating non-human voices and nature’s perspective into these assemblies, drawing from Amber’s experiences with Sea Change and impactful documentaries like My Octopus Teacher. It was a stimulating discussion that left me eager to explore new avenues for citizen engagement and policy making.

Olivier Schulbaum: Let’s start by talking a little bit about affect and how your work engages with it. How does your work at Future Natures intersect with the concept of affect?

Amber Huff: As we commonly use the term “affect” in everyday language, it generally refers to emotions and feelings, those sorts of experiences. However, there’s a lot of contestation around the concept of affect. It can be seen as an individualistic phenomenon, often used in clinical settings like psychiatry and psychology. But affect can also be a highly political and social concept. Thinkers like Spinoza, Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Brian Massumi have been influential in the philosophy and what’s called the “affective turn” in various research disciplines and philosophy. This has also influenced anthropology and human geography, advancing a social relational approach to affect.

This social relational approach is important beyond academic thought. It extends into the arts, performance, radical philosophy, and social movements. In this way of thinking, affect goes beyond individual emotions and feelings and how they affect individual consciousness. Instead, it’s better thought of as the embodied capacity and potential to affect others and be affected oneself within a social context. This capacity flows between bodies, which can include people, non-humans, and material entities. Affect plays a crucial role in shaping relationships, not just socially but also between our embodied experiences, social subjectivities, and our recognition of others as singular persons.

Given this orientation around affect, it’s challenging to talk about affect alone. It’s often called an ineffable concept because it’s difficult to describe these embodied, pre-cognitive ways of experiencing life and reacting to various encounters. To clarify for discussion, we can differentiate between affect, feelings, and emotions. Think of feelings as biographical and specific to a person—the way that person narrates their experiences, influenced by affect but filtered through their understanding and sense-making process. Emotions, on the other hand, are the social projections or expressions of those feelings. When we talk about affect, we’re referring to something that can be pre-cognitive, sensorial, and embodied, felt before we can articulate it, but it can also be post-cognitive.

Some forms of writing, particularly embodied writing, can evoke affective experiences more effectively than others

Despite its complexity, we can express and communicate our affective experiences, often profoundly, through storytelling and creative methods. Some forms of writing, particularly embodied writing, can evoke affective experiences more effectively than others. This is how I became interested in thinking with and through affect in my work with Future Natures. During the pandemic, I started using techniques of embodied writing to explore the experience of living through a period where societal rules seemed to change rapidly. This wasn’t just about lockdown rules but also about broader changes in understanding social organization, government responses to threats, and the power of vaccines.

Experimenting with embodied writing during this time resonated with ideas from weird fiction and fantasy literature. This led me to delve deeper into the spectral turn, considering how the atmospheres of places and landscapes affect us, which further led me into thinking about affect. This exploration has shaped my approach to affect and continues to influence my work at Future Natures.

Your work at the Center for Future Natures seems very oriented around the commons and commoning. How does this focus influence your exploration of affect and the ways people experience and enact alternative systems?

Amber Huff: Our work at the Center for Future Natures is indeed centered around the commons and practices of commoning. We are interested not just in the commons as objects but in how people experience and are motivated to build different systems than the dominant ones around the world today. A crucial part of this is situating alternative democratic practices, like commoning, within the current juncture.

We use storytelling, research, and the arts not just to discuss cases and instances of commoning but to situate these practices within the broader context of planetary changes affecting us right now. For example, we recently called for contributions on the theme of “strange natures,” which was highly successful. We received submissions from visual artists, zines, poetry, fiction stories, photo essays, and more. These works reflected on ideas of the strange and the uncanny, using notions of the spectral, the haunted, and the uncanny to understand how our experiences are made weird by globalization and capitalism.

These historical social forces have altered our experiences of landscapes and created a sense of wrongness when we enter certain spaces. Our daily experiences, especially during lockdowns, challenged our rational ways of thinking about time, space, ecology, agency, and power. The anthropocentric sense of mastery and control over the world seemed to collapse. For me, this is a marker of the Anthropocene—not the dominant narratives we hear about human supremacy and the so-called ‘end of nature’, but the ruptures and social and ecological breakdowns that become increasingly hard to ignore.

When we dig deeper into these dynamics, the myth of human control and mastery of nature falls apart. This critique, viewed through the lens of experience, meaning, and value, aligns with our ideas about the commons and commoning. It highlights the need for broad and radical responses to these challenges.

Olivier Schulbaum: Maybe taking it back to this idea of affect, I have a simple question. When you talk about collective threats or shared experiences that affect us differently, we could almost calculate an average affect in a specific community. Regarding activism, is affect becoming some kind of commons in itself? Is there a shared feeling or response that represents the voice of a movement, or is it important to maintain a diversity of affects to convey a stronger message to politicians and decision-makers?

Amber Huff: I think both situations are true. The intensity and mutuality of affect, its relational and social dimensions, are at the heart of many democratic movements and always have been, even if we haven’t always put a name to it. The notion of a movement itself resonates with being moved, being affected, and spreading that motivation, whether it be rage, anger, or a visceral sense of injustice. These intense feelings, though often negative, are crucial motivators for positive movements and reforms, opening up new ways of thinking in society.

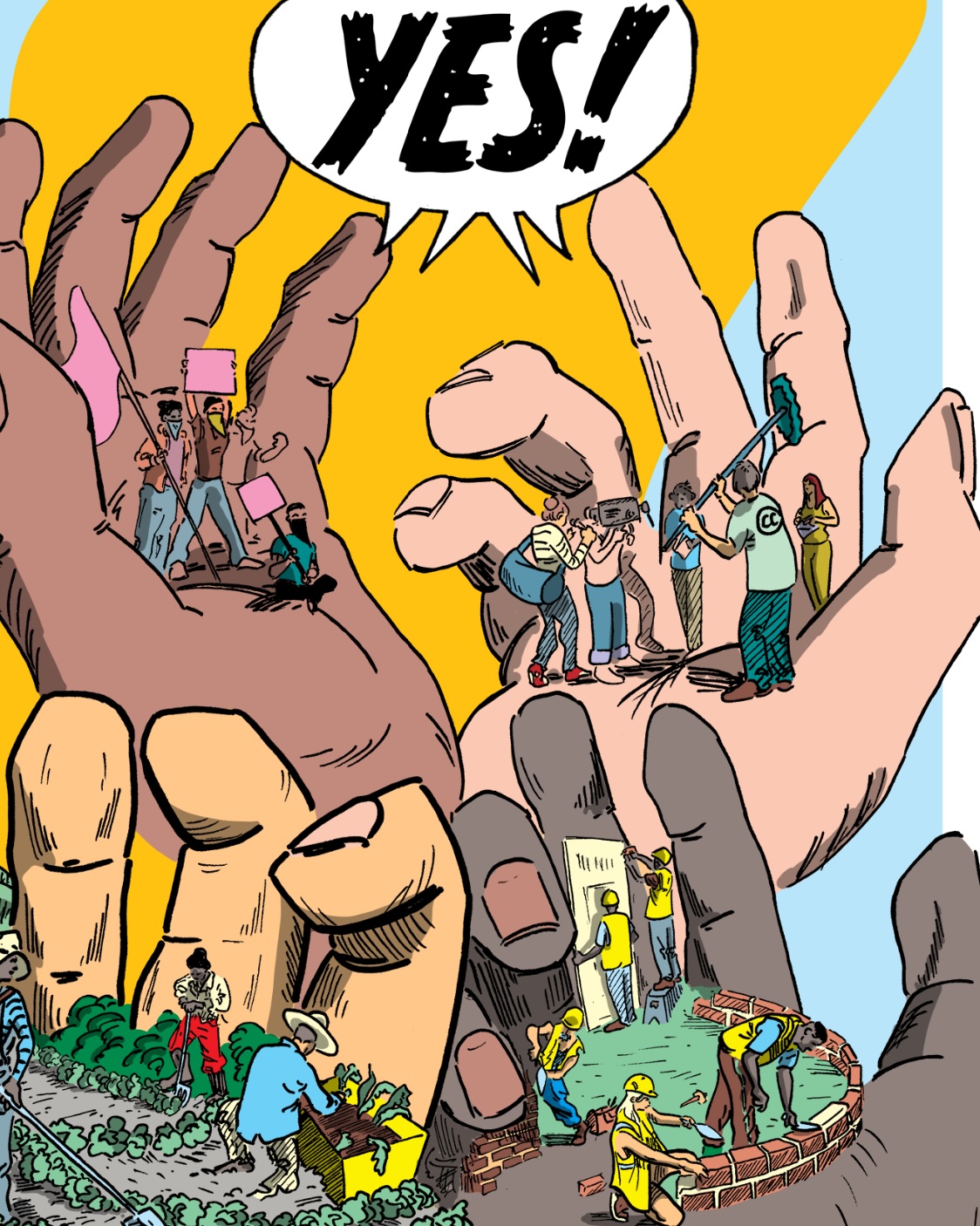

When we talk about these things, we’re discussing the affective dimensions of social movements. Being conscious of affect and affective perspectives can help us mobilize messages more effectively and communicate better about our movements and demands. This isn’t just about addressing leaders but also about fostering mutual understanding within our movements. Building a truly democratic society requires shifting away from individual motivations and recognizing that true democracy thrives in social contexts rooted in mutual respect and dignity. This respect involves upholding practices and ethos that honor individual differences while ensuring everyone’s right to thrive. This understanding is more profound than contemporary liberal forms of democracy, which often equate democracy with voting and lack substantial social accountability. Normalizing practices like consensus, solidarity, and mutual aid, recognizing difference, and creating affective atmospheres of care can influence broader notions of democracy by providing examples.

Olivier Schulbaum: Speaking of the intensity of affect in activism, I’ve noticed that movements can sometimes become overwhelmed by the sheer energy and emotion, leading to burnout. There are NGOs focused on social healing for activists. Do you think affect as a commons can be supported by such external entities to prevent burnout and ensure sustainability within movements?

Amber Huff: Yes, the intensity of activism can lead to fatigue and burnout, which is why care and mutual support are so vital. Normalizing care values means looking out for each other to prevent burnout. Ideally, there would be public funding for the care of those doing this crucial work. Universal basic income and social safety nets can help alleviate the pressures on activists, allowing them to focus more on their causes without the constant strain of ensuring basic living conditions.

As we face multiple, overlapping crises, we must learn from the past and avoid repeating mistakes, even as we encounter new challenges

However, we must also be cautious. Historically, welfare states have sometimes served to sustain economic growth at the expense of the environment. We need to be reflective about our demands, recognizing our interconnectedness with other people and the environment. As we face multiple, overlapping crises, we must learn from the past and avoid repeating mistakes, even as we encounter new challenges. Our struggles should aim at building a world that supports diverse forms of life and thriving, grounded in mutual respect and care.

Olivier Schulbaum: Let’s get back to Future Natures. You mentioned the concept of “strange natures.” Could you elaborate on how you use imaginative and creative methods to address concrete climate disasters? Can these methods be as effective when focusing on specific climate threats in particular regions?

Amber Huff: Absolutely, imaginative and creative methods can be very effective in addressing specific climate threats. The “strange natures” intervention aimed to open up ways of communicating about the everyday stories and emplaced relationships that come with living and dying on a troubled planet. Some of these stories are small, personal, and profound, while others are grand and fantastical. Ultimately, they all work toward opening up ways of thinking about our relationality with the rest of existence.

These stories often deal with how people process trauma related to changing landscapes, pollution, gender violence, racial violence, persecution, or colonialism. By highlighting these experiences, we foster a more careful and caring approach to our interactions with other creatures and our systems, inspiring thoughts on how these systems can change.

There is no silver bullet solution to the climate crisis. High-level political discourse has shifted from mitigation to adaptation because repeated international agreements have failed to address the root causes of our accelerating crises. However, by amplifying voices often drowned out in high-level debates and normalizing the idea that it’s okay to grieve changing landscapes and loss of life on Earth, we can initiate subjective shifts that ultimately have broader impacts on how our systems operate. Many people feel helpless when faced with news of genocide, massive storms, and other climate disasters. They recognize these issues are due to anthropogenic climate change but don’t feel personally responsible. Understanding power relations and identifying where we have the power to make a difference is crucial. Planetary framing of problems and solutions can make us forget that changes happen in specific places, where we can intervene.

For instance, emissions originate from certain locations, oil spills occur in specific regions, and the extraction of rare earth minerals for green technologies happens in particular places. These are the sites where intervention is possible. It’s not just about personal actions like recycling; it’s about more significant actions like shutting down mines if that’s what will help your community and environment. Whether it’s conducting research, expressing solidarity with those resisting socio-ecological violence, or taking direct action, finding where you can intervene can help address your grief and contribute to societal health. Intervening in specific places where change is needed can lay the foundation for building a different future and world.

When we talk about nature, we’re not referring to something outside ourselves. We are natural beings fundamentally intertwined with all systems. “Future natures” means changing the narrative from seeing humanity and the non-human world as separate entities to recognizing our mutuality and interconnectedness. This shift can help us build relationships based on care and respect rather than domination and exploitation.

Olivier Schulbaum: Let’s discuss visual cultures related to your work. How do visual cultures, such as comics and other art forms, contribute to creating more empathetic narratives around polarized issues? Particularly, can these methods be applied to the types of knowledge used in citizen assemblies, where data and expertise dominate, to help citizens understand how external phenomena affect them?

Amber Huff: That’s an excellent question with two key parts. First, using creative methods and engaging with visual culture, such as comics and various art forms, democratizes knowledge production. By breaking down barriers around academic knowledge, we make information more accessible and relatable. This democratization of knowledge empowers people to think critically about their surroundings and contributes to more pluralistic debates.

When information is restricted to certain channels, it can be used politically to suppress debate, hindering democratic participation. Therefore, finding ways to tell stories about the world that are more accessible and participatory is crucial. Creative methods can bridge the gap, making complex issues understandable and engaging for a broader audience.

Regarding citizen assemblies, there’s no inherent contradiction between using narrative arts and quantitative data. Each serves a different purpose and answers different types of questions about any given problem. Quantitative data provides insights into magnitudes and amounts, showing change over time and offering a broad view of an issue. In contrast, narratives and qualitative stories add depth, highlighting the multidimensional experiences of individuals.

For instance, if someone shares their experience of injustice, their narrative might include various components that qualitative data alone cannot fully capture. This personal story can spark a discussion, providing a nuanced understanding of the issue. To quantify the prevalence of such experiences, we can then turn to quantitative data, which complements the narrative by illustrating the broader context.

Narratives give us a deep, empathetic understanding of issues, while quantitative data helps us grasp the scale and frequency of these experiences

Combining these approaches allows us to present a fuller picture. Narratives give us a deep, empathetic understanding of issues, while quantitative data helps us grasp the scale and frequency of these experiences. For example, knowing how many people experience police violence is crucial, but understanding what police violence entails requires listening to the stories of those affected. In summary, using both narrative and quantitative methods in citizen assemblies and other participatory platforms can foster a more comprehensive and empathetic understanding of complex issues, making the information more accessible and impactful.

Olivier Schulbaum: Let’s talk about citizen assemblies, the Sortition Foundation typically recommends expert interventions and data reports. Consequently, the recommendations of citizens often mirror expert positions. At Platoniq Foundation, we advocate for a blend of different languages and data natures. Considering this, have you observed greater receptiveness to visual or oral storytelling in particular cultural contexts or regions? If so, what factors contribute to this receptiveness, especially when dealing with diverse participants from different continents?

Amber Huff: I haven’t noticed significant differences in how people respond to visual and oral storytelling across different contexts. Whether using comic books, illustrated maps, or participatory filmmaking—both documentary and story-based—these methods have been well-received across a wide range of settings. For instance, in Madagascar, these techniques resonate with everyone from rural farmers and foragers to policymakers. They are engaging and put a personal face on what could otherwise be dry statistics.

We’ve used these methods in the UK, the United States, South Africa, and elsewhere, and I’ve found a nearly universal appreciation for creative approaches. These methods are effective because they humanize data and make it more relatable and engaging than traditional reports or policy documents. Different methods and forms of evidence are suitable for different types of questions and often work best in combination. Creative methods are particularly valuable when communicating across significant social divides. Participatory filmmaking or photography, for example, can empower people to set the terms of the conversation, especially when discussing policies that affect their local area. So, I agree with you that the combination of different forms of evidence and storytelling can be powerful. While the specific mix might vary by topic or region, creative methods can significantly enhance communication and understanding. The challenge often lies in how receptive politicians are to these visual and narrative forms. Nonetheless, integrating participatory methods can activate a more inclusive and engaging form of dialogue.

Olivier Schulbaum: As part of citizen assemblies, there’s still a lot of work to do. Despite the participatory nature, policymaking often becomes technical. Politicians and administrators want to reach clear consensus, so no matter which creative forms are used, the output must be standardized policy recommendations. We had an example with a project on youth mental health using Legislative theater to produce recommendations. However, the consensus and energy around creative methods often get distilled into technical formats for politicians. How can we ensure that the transition from creative methods to policy recommendations retains the impact of those methods? Is this possible, or is it a lost cause?

Amber Huff: There’s definitely interesting work to be done in this area. While policy recommendations often need to be delivered in a specific, standardized way—politicians do love their bullet points—the content of those bullet points can still be informed by participatory and creative methods. For instance, the deliberations and consensus-building processes within a citizen assembly can draw on a variety of knowledge forms and creative outputs.

You might need to deliver the recommendations in a straightforward format, but the substance of those recommendations can be enriched by the creative methods used during the assembly. For example, you could create a small film featuring oral testimonies from youths discussing their experiences with mental health inequities. The film could directly address and reinforce specific policy points, making the recommendations more compelling and humanized for policymakers. Each community has different dynamics and relationships with policymakers at various levels, so it’s crucial to experiment with and adapt creative methods to fit those contexts. Combining clear, concise policy recommendations with supplementary creative materials can effectively communicate the depth and significance of the issues being addressed. While it requires innovation and creativity, this approach can bridge the gap between participatory methods and formal policy processes.

Olivier Schulbaum: My last point ties into your reflection that we, as humans, are part of nature. Usually, in citizen assemblies, politicians avoid very polarized issues. For example, in Catalonia, there was an assembly focused on racism in renting houses. It was very experimental. We’re now piloting global citizen assemblies on the future of the oceans, and we’re exploring how non-human elements can participate in these processes. How would you visualize or express these natural voices? How can we ensure their representation in an assembly, and is this too experimental for politicians?

Amber Huff: Colleagues and I have worked with a group in South Africa called Sea Change, known for the documentary My Octopus Teacher. We researched the film’s impact and found diverse responses—some negative, some empathetic towards non-human creatures. This shows how visual storytelling can evoke empathy and emotional responses, fostering connections between people and non-humans.

In an assembly context, telling stories about encounters and embodied experiences with non-human environments could be effective. This might involve people sharing personal stories about their interactions with nature, emphasizing their emotional and sensory experiences.

However, incorporating these narratives into policy recommendations is challenging. It requires innovative communication strategies that resonate with both citizens and policymakers. While I haven’t seen it done effectively yet, I believe combining these personal narratives with traditional policy formats could make a significant impact. Maybe we can continue to explore and experiment with these methods to find the best way to integrate them into participatory processes.