Interviews

Renata Avila overnance needs fiesta: Joyfully reconnecting the open movement with grassroots movements

In this provocative conversation, Renata Avila, a Guatemalan lawyer and activist specialising in technology and intellectual property, who works at the intersection of human rights and technology, reflects on the transformations, challenges and potentials of the digital commons movement.

In dialogue with Olivier Schulbaum and Cristian Palazzi, she highlights how the privatisation of digital infrastructures and the institutionalisation of the movement have moved the Commons away from its roots in grassroots movements. The interview addresses crucial issues such as the need for sustainable governance models, the interaction between the digital and the physical in platforms such as Decidim, and the role of art and culture in the construction of narratives capable of countering populist manipulation.

Pointing out how Wikileaks marked a critical turning point, separating the waters between a more institutionalised movement and radical, community-based activism, he invites us to imagine how the digital commons can connect with other struggles such as climate and territorial justice, promoting alliances between the local and the global.

Olivier: Where is the movement of the commons heading, and how has your experience as a human rights lawyer and digital activist influenced it? From your perspective of commons-based governance, do you think there is something we need to redefine?

Renata: More than my human rights experience, the interesting thing has been to realise that we don’t need super-specialised legislation to address digital issues. Fundamental rights already cover much more than what a fragmented regulation with digital charters or specific principles can offer. I think we missed the opportunity to expand rights.

From the point of view of the commons, it is more effective to start from general principles and adapt them to emerging technologies, rather than what has been done in recent years: detailed and excessive regulation, as we have seen in the European Commission and in several countries. I think we could have adopted principles of governance of the natural commons and community or social dynamics, learning from indigenous practices such as distributed governance and community conflict resolution.

However, a mercantilist view prevailed in the regulation of digital rights. Another approach that could have been useful is to assess technological impacts from a community perspective, beyond the individual. Although there are figures such as Max Schrems who have made great strides in digital rights, their vision is very much focused on ‘my data, my rights’. There has been a lack of a perspective that looks at the collective and the community.

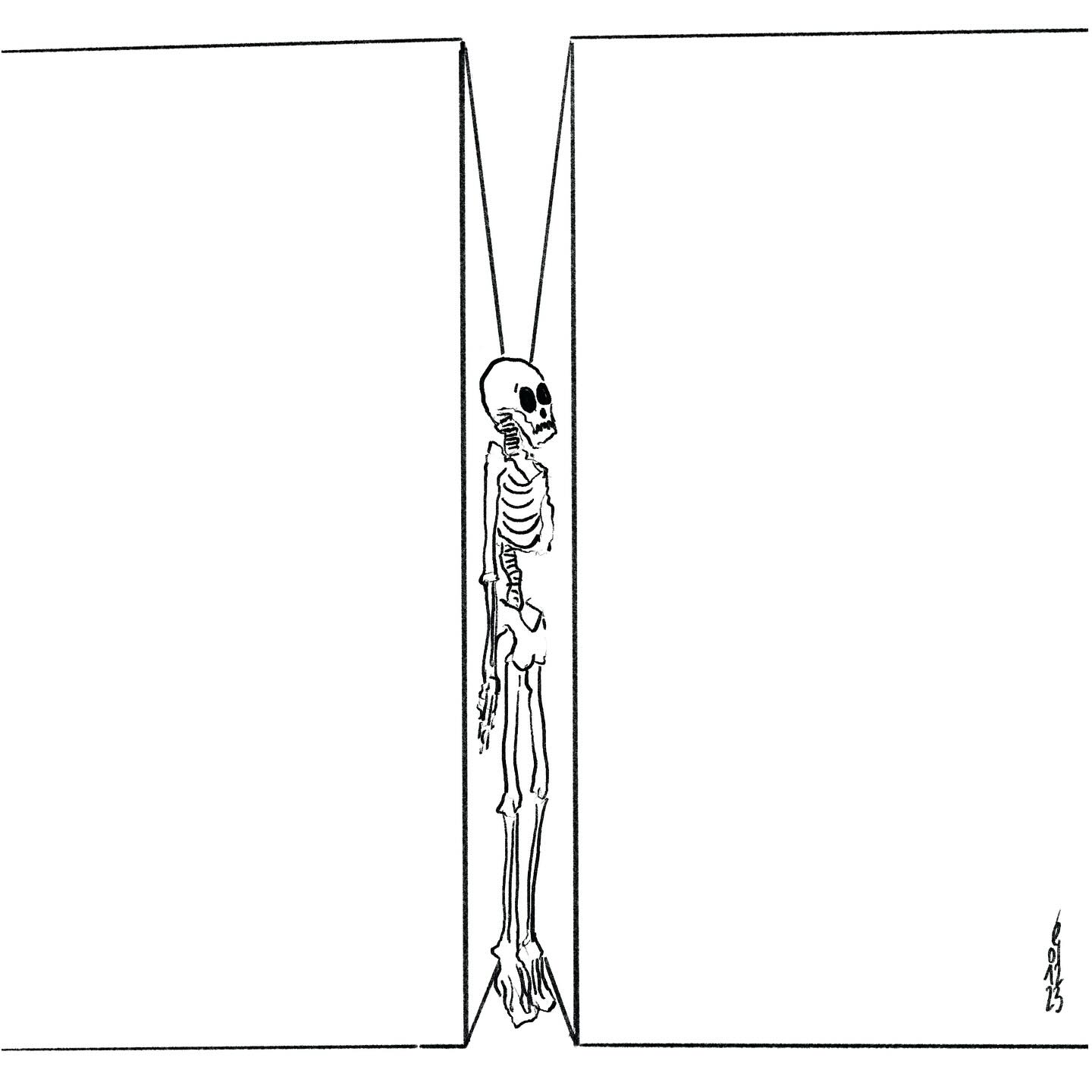

undefined

Olivier: From your position as Executive Director of the Open Knowledge Foundation, what are the biggest tensions we see within the commons movement, especially in the balance between openness, inclusiveness and privacy?

Renata: More than conceptual tensions, I think we face a generational tension. The Commons movement went from being a collective citizen effort to becoming institutionalised in organisations like the Wikimedia Foundation or the Open Knowledge Foundation, which started to receive large sums of money. This professionalised activism, turning it into a 9-to-5 job, and completely displaced community building, especially intergenerational community building.

A key moment was 2010, with Wikileaks. It was a turning point that showed who was willing to take risks for their principles. But it also marked the ‘death of community’: many distanced themselves out of fear and a vision of ‘this is too much, too much freedom’ was promoted. Collective access to unfiltered information might have changed our understanding of the world, but the movement was divided. On the one hand, some demanded immediate systemic change; on the other, many chose to withdraw.

States reacted in two ways: by funding and controlling institutionalised organisations, which professionalised citizens’ activities, and by criminalising key figures such as Julian Assange and Aaron Swartz. This weakened the movement and fractured its foundations.

Then the Edward Snowden revelations shifted the focus to privacy, leaving fundamental battles such as access to knowledge behind. The obsession with privacy obscured the original spirit of collaboration and creation of the commons.

Today, the movement is dominated by an institutionalised vision. Governments took advantage to control through funding and, later, defunding. This left the movement fragmented, ageing and disconnected from current struggles.

The key is to reconnect with the new generations. They have a disruptive vision of the system, but they need tools and support to appropriate the logic of the commons. It is no longer worth trying to win back middle generations who prioritise conformity. We need to focus on young people, who have the potential to revitalise this movement with a bolder and more transformative vision.

Wikileaks graffiti on Le Plateau

Hubert Figuière from Montreal, Canada

Olivier: How can we build a new narrative for the digital commons that not only connects to current struggles, such as climate justice or social reconstruction processes in crisis contexts? What key elements should guide this narrative to be transformative and effective?

Renata: We are in a much better position now to resist the privatisation of digital infrastructures, but only if we embrace a common vision of the technology we want. It is not about replicating Silicon Valley, but about creating ‘good enough’ technologies that mediate our spaces. The most important thing is not the code, but the people and the rules of governance.

If we want to transform digital spaces of resistance into spaces of creation and coexistence, we need to seriously review our governance systems. This is where the commons has a lot to offer. For example, we have talked about governance models based on the commons, and while there are successful cases, much work remains to be done to define clear principles and translate them into workable practices. The key to building sustainable digital alternatives is not in the code, which accounts for just 10% of the effort. It is 60% in governance models and 30% in sustainability.

We need governance that allows communities to federate, that is functional and that responds to people’s real needs. So far, we have focused too much on code and data, but we cannot separate digital communities from their governance structures. That is the greatest contribution that a new era of the digital commons can offer: governance models that will eventually become the norm, replacing current systems.

Moreover, governance cannot be just about rules: it needs fiesta.We need music, food, dance and joy. Our movement used to be more fun; now it is full of post-its and formal meetings. We need to bring back the party, because sharing the good things in life is as important as creating functional structures. Governance and partying must go hand in hand to build truly collective and human digital spaces.

Governance and celebration must go hand in hand to build truly collective and humane collective spaces

Olivier: Decidim, as an open source platform, allows to adapt to different needs thanks to its flexibility. However, the use of Ruby as a programming language represents a challenge, as its high costs make it difficult to access for many communities looking to manage their own Decidim. Do you think this choice limits its potential as an inclusive and sustainable tool?

Renata: This is a common problem in the development of open technologies. In the case of Open Data Editor (newly updated), we had to rewrite the whole code because it included unnecessary functionalities that nobody was going to maintain. Sustainability is key: tools need to be low-cost and easy to maintain. We don’t need perfect performance, just good is good enough.

To achieve this, it is essential that communities define their priorities from the outset. This ensures that tools are useful and sustainable, without relying exclusively on developers or technical interests.

One example: last year we launched an initiative called Tech We Want, focused on low-cost technologies that are easy to maintain and designed to last at least ten years. These tools should serve specific purposes without collecting unnecessary data.

Creative Commons guiding contributors

CC BY-SA 3.0

Olivier: How can we build a new narrative for the digital commons that not only connects to current struggles, such as climate justice or social reconstruction processes in crisis contexts? What key elements should guide this narrative to be transformative and effective?

Renata: The genocide in Gaza offers a crucial starting point for this reflection. It was an example of how technologies and narratives can combine to completely ignore basic principles. This kind of crisis, like the transition processes in the Middle East, shows us that a commons-based approach could play a transformative role in rebuilding societies.

Moreover, the climate crisis and its associated disasters highlight the urgency of connecting the digital commons with other commons. We cannot treat the digital commons in isolation; we need to weave links with social and climate struggles, highlighting both the differences and the connections between them.

The most important mission now is to integrate the digital commons into a broader framework that addresses these global crises collectively. An effective narrative must emphasise these connections and offer inclusive solutions that respond to both local and global challenges.

It is essential to maintain cohesion and congruence in common missions in order to transcend small spaces and have a strategic impact on public policies.

Cristian: Most politicians, especially populists, don’t appeal directly to the truth, but manipulate emotions to win support, even if they say things that make no sense. We have lost recourse to reliable data and consensus, how do you think these narratives can be combated, and could art and culture play a role in this?

Renata: There are two complementary ways to connect grassroots activism with institutional policies. On the one hand, some community initiatives can work without being linked to institutions. For example, locally organised food banks have a horizontal and sustainable impact if the community is supportive, coherent and politically congruent. But something is also lost if these initiatives do not take on an autonomous and collective dimension, regardless of who is in power.

It is essential to maintain cohesion and congruence in common missions in order to transcend small spaces and have a strategic impact on public policies. If a community works on green spaces or supports children, it must be able to use its experience and cohesion to intervene and propose informed solutions in public policy.

However, a common problem is that when a progressive leader comes to power, movements often dissolve to join the government, leaving communities behind. A good example of how to avoid this is Morena in Mexico, which left leadership at the grassroots to ensure the continuity of the movement. It is necessary to think about both the movement and the party, and to build counterbalancing mechanisms.

In addition, intergenerationality is key in local communities. In Europe, there is a lot of talk about policy disconnection, but community cohesion has also been neglected. If the poorest peasants in Brazil have achieved this without resources, there is no reason why it should not be possible here as well.

XR Declaration of Rebellion Den Haag - 15 April

Extintion Rebellion NL

Olivier: Movements like Extinction Rebellion are an example of activism that connects resistance with deliberative democracy. Although they have a performative and Western approach, what do you think of their methods and digital tools?

Renata: Movements like the Landless Movement in Brazil offer a more holistic model. They not only resist, but also propose clear solutions, with educational and solidarity spaces. This contrasts with more performative approaches such as Extinction Rebellion. However, both have something valuable to contribute.

The challenge is to connect digital struggles with other common struggles, such as territorial or climate ones. The key is to weave these connections and highlight how the digital commons can strengthen other urgent struggles, such as climate or social struggles.

This article is part of a series of publications in the context of the Convergence of Commoners, a transformative retreat exploring digital commons, data democracy and creative activism.