Deep dives

Democratic Funding: Citizens choose their future. Limits and hopes in Participatory Budgets and Matchfunding

Hypothesis

For many people, democracy is summed up in voting for political representatives once every four or five years and paying taxes trusting that they will go to the best possible projects to sustain a well-being society.

Others, however, understand that citizen participation should be greater, they aspire to be an active part of decision-making and ask themselves the same question: are there processes that are more democratic than others when it comes to deciding what public money is spent on? ?

In this article we will talk about Participatory Budgets and Matchfunding, two tools that have already allowed thousands of people to decide what to allocate public resources to and make social welfare initiatives a reality. The first thing will be to give a brief definition of each one, then we will delve into their strengths and weaknesses, to finish by pointing out some of their main challenges as well as achievements that we already celebrate.

Various studies show that youth are more likely to vote in local and national elections after participating in participatory budgeting: they are also more likely to enter municipal buildings, get involved in politics, talk to a public official, volunteer and trust their abilities.

Why do we think this question is relevant?

Participatory budgets can be one of the ways to recover credibility in institutions, because, as Molina (2) very well says, participatory budgets «not only try to participate in decision-making, but also put into practice the conditions and mechanisms to make this condition possible, which implies improving and making management transparent, which is the way to eradicate corrupt conduct».

Matchfunding in turn and as collective financing of projects, together with the receipt of citizen contributions through crowdfunding campaigns, allows organizations to allocate their own resources to projects already validated by social support.

At this point we believe it is useful, both for those who have already mastered the issue and for those who are now discovering these concepts, to dedicate the following section to delving into both tools.

State of the art

Through participatory budgets the citizenry can present projects and decide where the money goes, but the projects are executed by the Administration, with all its limitations in the process, integration of diversity and final execution.

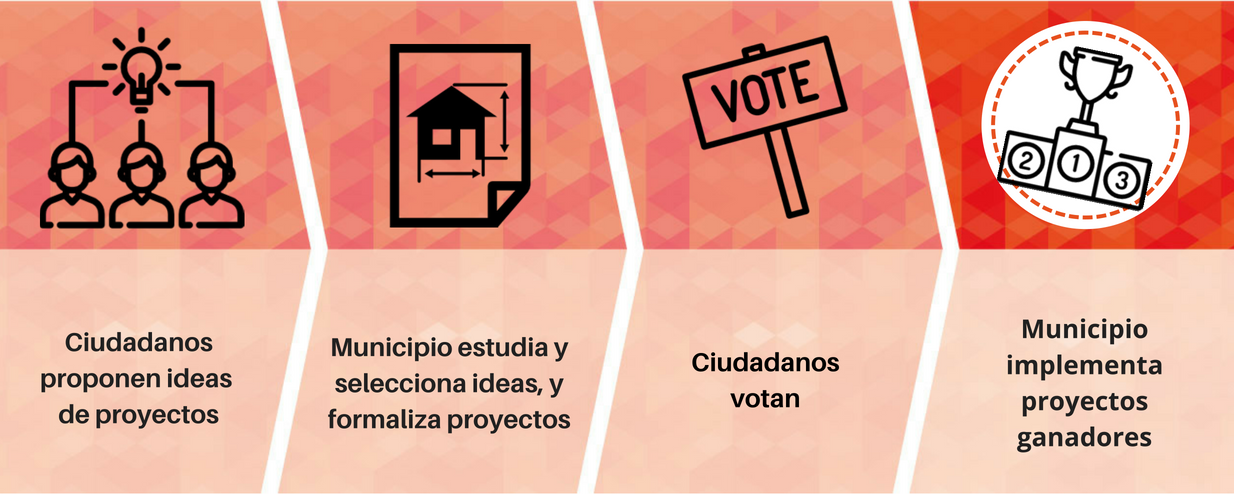

(1) Citizens propose ideas for projects (2) The Administration studies and selects ideas, and formalizes projects (3) Citizens vote (4) The Administration implements winning projects

Comunicaciones EVoting

In matchfunding, citizens present and execute an initiative through a crowdfunding campaign the costs of which are covered equally between donors and the Administration.

Participatory budgets appear for the first time as a participatory tool at the end of the 1980s in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, in the coincidence of three specific situations:

- Coming to power of a progressive party that has the implementation of this tool in its program.

- Existence of a network of social organizations that gained strength thanks to their struggle against the existing military government in the 1980s.

- Need for local governments to respond to needs not covered by the central government.

Thus, during the 1990s, the citizens of Porto Alegre decided to allocate almost 25% of the budget to improve the sewage system and increase access to the water supply. Although to achieve this they had to face various difficulties: legal in proposing certain proposals and communicative in explaining the methodology to a population with a high degree of illiteracy and fearful of political instrumentation. As cities in other countries tested the model, they encountered the same obstacles, being in 2001 when the first participatory budgets were proposed in Spain, specifically in Córdoba, Las Cabezas de San Juan and Puente Genil. At a media level, the best-known processes will be in Madrid and Barcelona, as they will be carried out by recently formed political parties, with strong reluctance from the opposition and with a very high investment. We highlight, for example, that thanks to the participatory budgets of the Madrid City Council, the Consul platform, a free code tool that facilitates the participatory processes of entities or administrations, is beginning to be used in the rest of Spain.

At present, many city councils still do not dare to put them into practice or dismiss them due to their quantitative dimension (in Spain, between 0.5% and 1.5% of the population that can vote participate) while they underestimate the qualitative dimension of the social participation processes when they provide the government that promotes it with greater transparency, a new two-way communication channel with the population, contrasted and prioritized information on the needs of the population, increased associationism, involvement of the population in important decisions and rapprochement to a more participatory democracy.

At the same time, the participatory budgeting methodology is very diverse and we consider it interesting to summarize here the typology proposed by Sintomer, Herzberg and Röcke based on four criteria (1) Origin of the process; (2) Organization of meetings (neighborhood, city and/or thematic assemblies; closed vs. public meetings, etc.); (3) Type of deliberation (discussion topics, discussion modalities, etc.); (4) Position of civil society in the procedure (type of participating citizens, co-elaboration of methodology, etc.) where we can identify six different models and begin to glimpse their level of democratic participation:

- Porto Alegre adapted for Europe

- Participation of organized interests: secondary associations, NGOs, unions and other organized groups are main actors, in a neo-corporatist logic born in places where the previous participatory tradition has been based on the contribution of associations and interest groups to the definition of policies public in particular sectors.

- Community funds at the local and city level: There is a fund for investments or projects (in the social, environmental and cultural areas) relatively independent of the municipal budget, which does not come, or comes only in part, from the local administration and above all which the city council does not have the last word regarding the acceptance of proposals. It depends on a commission or assembly that generates the priorities. Organized groups, such as local or community associations and NGOs, are at the center of this model and companies are excluded. The deliberative quality can be considered fair, since several meetings are held with a manageable group of participants.

- The public/private negotiation table: Private companies and possibly international organizations raise part of the money, allowing the private sponsor to influence the design of the procedure, while the citizenry, which does not give money but asks for it, only plays a secondary role. This model can develop when international actors try to include citizen groups or NGOs in public/private partnerships.

- Proximity participation: They include merely consultative processes and the participants here do not vote or develop priorities for the projects. They do not pursue social ends and there are no distributive criteria in the process. Rather, it is a process of “selective listening” where the local government calls individual citizens through media announcements, letter or personal contact and can freely (and arbitrarily) integrate some of the proposals into its public policies after the process. participatory. At the level of the city as a whole, this model is no longer about investments, but about general policy objectives (“a beautiful city”). The term “proximity” refers to geographical, in the sense of organizing several meetings within the neighborhoods instead of a single meeting in the town hall, and of close contact between the municipal leadership or administration and the citizens by organizing open meetings to respond to citizen concerns.

- Consultation on public finances: it is part of a general modernization of the local bureaucracy that tries above all to make the financial situation of the city transparent with information on the general budget through brochures, the Internet and press releases. In general, the deliberative quality of the model is low, since a discussion limited to one or two meetings a year can hardly produce great effects, unlike the ‘proximity participation’ model, where citizens sometimes work in small groups that they meet repeatedly over a longer period of time. In both models, accountability is low with respect to making proposals and the autonomy of civil society is weak.

Matchfunding, for its part, is the evolution of the collective financing of projects through crowdfunding campaigns on platforms such as goteo.org, born within the Platoniq Foundation for the promotion of initiatives focused on social innovation and the first national platform with matchfunding (in 2013), as an innovative co-financing model by which a public or private institution or an individual contributes funds to complement (doubling or increasing ) the amount raised by a campaign project, promoting co-responsible investment and expanding the impact of projects that have the support of civil society.

We know that there are numerous institutions interested in promoting and supporting creative projects in the field of culture, research, technology or science. Sometimes they find it difficult to make their contribution visible, to reach the right industry and audience, or to get communities involved. Institutions are also looking for ways to help these projects raise funds, better manage high administration costs, and ensure long-term project sustainability. A matching financing program provides a powerful tool to accomplish all of the above.

In counterpart financing, an institution makes a sum available to develop a specific area (culture, education, etc.), then calls on the community to present projects in this area and calls on the general public to commit. with the money. The crowd supports a specific project by making small donations of funds that the institution matches with the same amount. For example, if the crowd donates €1,000 to a specific project, the matching funding institution (a public or private organization) will also provide €1,000, thus increasing the total project budget to €2,000.

Thus, matchfunding programs are calls to promote projects or organizations through financial aid according to the criteria defined by the collaborating public and private institutions. The beneficiaries must go through a crowdfunding campaign and a training program to validate the interest of the public and the viability of the proposal. Based on the success of the campaign, financial aid from the collaboration agreement with the collaborating public or private entity is also added.

For both public or private entities and organizations as well as individuals, matchfunding allows funds to be distributed through a model that promotes “efficient excellence” thanks to citizen participation, agility, transparency and capacity building. In the event that the funds are managed responsibly, as is the case of the Platoniq Foundation, all contributions can enjoy significant tax relief, being in the case of individuals, up to 80% in the section of the first €150.

For public or private entities and organizations, it is a way of conveying part of their skills and programs in an innovative way, as well as their commitment and social responsibility policies, using the potential of technology. In this way, it allows them to reach an ecosystem of civil society that, on their own, they do not reach so easily. They also obtain other advantages, such as participating in the generation of forms of collective knowledge and socially innovative projects, proximity and direct dialogue with emerging communities, visibility and recognition linked to projects related to the commons, etc.

Matchfunding is, like crowdfunding under the principle of co-responsibility, an opportunity offered to the institution to expand its impact, collaborating with new communities and audiences and involving them in its mission, which in turn probe and see its proposal validated through the active support of donors.

Two paradigmatic cases of this combination of crowdfunding and participatory budgets that we call “Matchfunding” are the call Metakultura, for its part it has already accumulated 6 successful editions (2016-2021) with a total of 94 projects financed and €886,871 distributed, as a program promoted by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa, which contributes up to €70,000 to promote cultural projects in the province, as a tool available to cultural agents to finance initiatives that enrich and strengthen the local fabric, as well as “Conjuntament”, which means “in cooperation” in Catalan, carried out by the Barcelona City Council in 2018, together with the Goteo platform and the Barcelona Activa organization, with the aim of financing social projects proposed by citizens, connecting deliberative democracy with the public budget with which 22 co-initiatives went ahead. financed through 2,629 contributions with a total distribution of €231,336, between citizen donations and the €96,000 contributed in matchfunding.

How do we approach the question from Platoniq?

Representation of project promoters avoiding their responsibility in the execution of the project

Take the Money and Run (Woody Allen)

In this section we are going to take out the magnifying glass and do an exercise that is as painful as it is necessary. If there are many virtues, there are not a few weaknesses or challenges that are experienced in practice. We identified three aspects as the most sensitive: disclosure of the proposal, project evaluation and accountability.

Dissemination of the proposal: We design ergo We decide

Both tools are still unknown to most of the population, whose confidence in their ability to actively participate in society has been undermined along with the value they give to their political representatives.

The ability to drive a serious process with clear rules also requires an active civil society and a local administration and executive who have learned to cooperate rather than compete to achieve significant results.

The current coexistence of “pure” participatory processes, which we have called the Porto Alegre model, along with others labeled as such but executed more as a “show” (for a single politician or the city as a whole) of democracywashing than a real device of citizen participation, harm the little faith that part of the empowered citizenry still treasures. In this situation, it is crucial to maintain a critical distance and not confuse ideological discourses and real achievements, as well as to continue developing decentralized tools that facilitate initiative and organization from the bottom up, as we find in [Decidim.org](https://decidim. org/es/), a digital platform with open infrastructure that includes code, documentation, design, training, a legal framework, collaborative interfaces, a community of users, facilitators that help people, organizations and public institutions to self-organize democratically in all scales.

Evaluation of the projects: beyond the menu and the letter

Cooking Democracy

Svetlana Malysheva

Each restaurant manages its production costs by preparing a series of widely consumed dishes within a not very extensive list at an affordable price (menu) together with a wider offer at a higher price (card). The service will be just as attentive, but the higher the purchasing power, the more options. Can we imagine a restaurant that invites customers to suggest new dishes to be added and enjoyed on subsequent visits?

For many of the people who have experimented with Matchfunding or Participatory Budgets, the feeling may be very familiar and similar: they are invited to the table of democracy to choose, dress and enjoy a variety of projects… whose offer and form of access has been “cooked” from inside doors.

Thus, in the Matchfunding calls, the choice of projects is the responsibility of the promoting entity and/or the crowdfunding platform, while in the ‘Porto Alegre in Europe’ and ‘Community Funds at the neighborhood and city level’ models, a ‘empowered participatory governance’ (Fung and Wright, 2003) and the citizenry directly assumes decision-making power (Gret and Sintomer, 2005), which enables the emergence of a public ‘strong power’ (Fraser, 1996: 89), while the models of Proximity Participation and Consultation of public finances are only consultative and the models of participation of organized interests and public/private negotiating table can give decision-making power to the participatory device, but they can hardly make political and social changes possible fundamental.

Would it be possible to receive project “commissions” from citizens and thus crowdfunding platforms, together with the administrations promoting Participatory Budgets, find a chef to cook them on demand?

Accountability: Where’s Wally?

Putting the focus on the people responsible for the project is as difficult as finding Wally

Martin Handford

- What happens if a project breaks the crowdfunding rules?

- Who is responsible for completing a project as promised?

In all project selection there is a trust and safety team that thoroughly reviews each proposal and takes the maximum existing precautionary measures, however it is the responsibility of the creator of the project to complete it. Although in some participatory processes there may be intervention in the creative process, neither the crowdfunding platforms nor the institutions manage their compliance.

This system of trust shared with the co-financers, who ultimately decide the validity and value of a project by supporting it, is paradoxically the biggest disappointment when the initiative does not keep its promises.

Europapress cites the case of budgets participatory initiatives in Madrid and the gap between approval and materialization, since a large number of citizen proposals had to be executed in several annual installments due to their magnitude or complexity and they indicate that “in fact, between 2016 and July 2019, of a total of 1,214 participatory projects, 998 were not executed, which represents 82 percent”, reaching the point where at present and as certified by the Official Gazette of the Madrid City Council (BOAM), they have already been declared “supervening unfeasibility” the 182 projects](In Madrid, for example, we read in [El Diario.es](https://www.eldiario.es/madrid/somos/noticias/ayuntamiento-madrid-entierra-182-proyectos-ciudadanos-carmena_1_8299637 .html) citizens who received enough votes to pass during the the editions of the years 2016, 2017, 208 and 2019.

Bonus Track: Without us there is no democracy (feminist)

20th century feminist struggles

Museum of London (Anonymous)

Modernization theories suggest that socioeconomic development fosters improvement in the lives of all citizens, including women, as society transforms from agrarian to industrial to post-industrial. Furthermore, Inglehart, in his revised theory of modernization, states that modernization brings socioeconomic and cultural changes that result in greater gender equality in politics (Inglehart & Welzel, 2005). However, global gender statistics do not reflect this claim. Throughout the world, women are marginalized in politics, and this is true regardless of the level of economic modernization within countries. A revealing fact is to verify that in the 493 cities with more than one million inhabitants, there are only 29 female mayors and of the 27 megacities that have more population than some countries, none was directed by women until 2015 (United Cities and Local Governments, 2015 ).

The impediments to women’s political participation can be broadly categorized into three large groups: socioeconomic, political, and sociocultural barriers. Key socioeconomic barriers identified include family responsibilities, lack of education, and finances. On some occasions, violence and harassment around public activities in general and politics in particular are explicitly mentioned as a serious problem, in addition to the negative attitudes of male politicians and the lack of initiatives by political parties. to ensure greater female participation in the organization and hierarchy of the party, dissuading women’s access to politics.

Could then a decentralized participation in space and time, such as participatory budgets and crowdfunding, be a gap where democracy made its way? We have the data on the participation of women in platforms such as Decidim, AhoraMadrid or Goteo to prove it.

More questions for reflection and analysis

- If we improve the disclosure of the proposals, will we improve citizen participation?

- Should we "repair" our democracies or reimagine them?

- Who can monitor the legitimacy of a participatory process?

- Is participatory washing an incurable endemic disease or a stumbling block to overcome?

Call to action

If you have experience or information on these issues that help us better understand the needs and existence of new citizen empowerment tools, contact us! We want to meet you and talk with you. You can find us at info@platoniq.net.

References

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/18/us/participatory-budgeting-shari-davis.html

- A. B. Ruble, «Introduction: Globalism and Local Realities-Five Paths to the Urban Future», en M. A. Cohen (ed.), Preparing for the Urban Future, Washington, 1996, p. 1, citado por J. Molina Molina, Los presupuestos participativos. Un modelo para priorizar objetivos y gestionar eficientemente en la Administración local, Pamplona, Thomson Reuters, 2010, p. 342.

- Fung, Archon y Wright, Erik Olin (2003), “Thinking about empowered participatory governance”, en Archon Fun y Erik Olin Wright (editors), Deeping democracy, Londres, Verso.

- Frase, Nancy (1996), “Redistribución y reconocimiento: hacia una visión integrada de justicia del género”, New School for Social Research, Nueva York

- https://www.publicdeliberation.net/how-participatory-budgeting-can-strengthen-civil-society-political-participation/