Deep dives

What is the role of cultural heritage institutions in the spread of misinformation?

Hypothesis

Covid-19 has exposed and amplified certain cracks and societal ills and among them has been the spread of misinformation and hate speech against various social groups. The question presented to the fourth task force composed of: Rasa Bočytė, Claudia Cacovean, Marta Anducas, Oyidiya Oji and Nadia Nadesan in the InDICEs bootcamp was essentially to understand the impact of misinformation on society and the role that galleries, libraries, archives, and museums can take in addressing it.

The pieces of this puzzle are many, so in the first phase of creating an overarching idea Oyidiya Oji, our task force leader, asked us to start writing questions that we saw arising from available data. We initially took our data from the following open dataset and report:

- ESOC Misinformation Data Set (External link) from Princeton University. This dataset collected posts from users spreading misinformation during the pandemic in 2020.

- The impact of disinformation campaigns about migrants and minority groups in the EU (External link). The analysis explores the impact of disinformation activity targeting minorities between 2018 and 2021.

Five themes arose from our questions:

- Channels/ modes of misinformation: the digital platforms and channels that influence how misinformation spreads;

- People behind the data set: people who are targeted by hate speech, and motivations of people who spread misinformation;

- Past, history, narrative: misinformation is not a new phenomenon and has historically repeated the same pattern of exploiting the most vulnerable or the most “other” members of societies;

- Power dynamics: misinformation that takes the form of hate speech is based on historical unequal power dynamics that discriminate

- The role of institutions like GLAMs (galleries, libraries, archives and museums): heritage organisations who shape historical narratives and public memory have a role to play in collecting and presenting counter-narratives that challenge historical stereotypes and injustices.

Taking into account the different themes, we formulated the following hypothesis to inform our investigation:

H1. Misinformation during the pandemic has been built on and reinforces historical unequal power dynamics.

H2. Digital media has amplified the harm of hate speech.

H3. Cultural institutions can and have acted as agents to facilitate dialogues and reflections that challenge the discriminatory narratives of misinformation.

Research

Initially, our research involved analysing our two main resources and comparing them to find similar themes and facts to create an overarching narrative that captured our analysis. An additional aim was to look for interventions, expositions, and initiatives from GLAMs that addressed misinformation in the context of epidemics and discrimination.

A salient theme was the creation of the ‘other’ in misinformation to create animosity or hate towards communities and marginalized groups seen as a part from the idea of a ‘homogenous nation or state’. This theme has occurred over history and appeared during several different epidemics from the AIDs crisis to Yellow Fever, and the Spanish Influenza. A result from creating an ‘other’ that the report reflected was that creating the other emphasizes disparities and creates distinct divisions across lines of race, ethnicity, and culture where different geopolitical interests are at play. So then, what can cultural organizations provide to challenge historical inequalities and critically think about the purpose behind hateful misinformation?

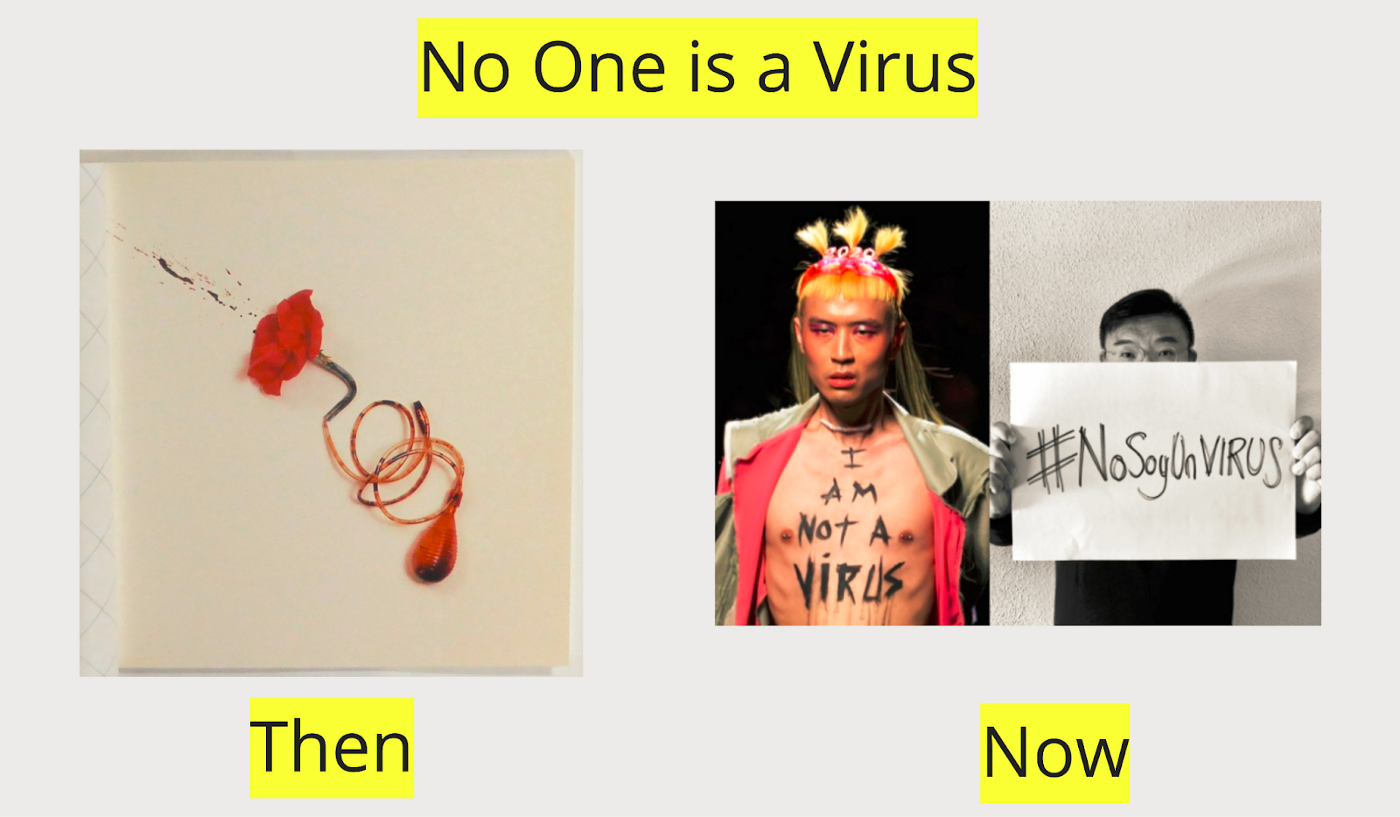

In our search, it was difficult to find examples of how GLAMs addressed epidemics or hateful misinformation of the past. Many of the examples were based on each task force members’ memory of an exhibition or relevant examples that might relate. One such example from our collective intelligence was the work, Lethal Weapons. In Lethal Weapons, artist Barton Benes challenges the audience with humor on their notion of the peril present in the blood of individuals living with HIV and AIDs. Benes, an individual living with HIV, filled everyday objects such as a perfume bottle or squirt gun with his blood which were then converted into ‘lethal weapons’.

Lethal Weapons: Venomous Rose, 1993. Barton Lidicé Beneš

Courtesy of Pavel Zoubok Gallery

‘These provocative pieces confront HIV/AIDS head-on, blending political activism, visual poetry and a wicked sense of humor, forcing viewers to face their fears of death and transmission.’ In our research we were in search of similar examples of exhibitions or initiatives by GLAMs that encouraged critical thinking and reflection on the impact of misinformation and pandemics, especially in terms of approaching the polemic themes of today’s misinformation with a more historical perspective. Perhaps we are not ‘going through exactly the same thing that happened in 1917, or the polio epidemic in the mid-20th century, or the early days of the AIDS pandemic primarily in the 1980s [however] each one of these historical examples is simply a useful lens to measure ourselves against, and to better understand some of the social…complexities that we’re seeing right now.’ However, few examples were available just through searching the world wide web. So as the bootcamp progressed the hypothesis became less of a statement to prove or disprove but an imperative initiative to situate GLAMs as a cornerstone space for people to challenge, rethink, and critically understand misinformation.

Visual Data Narratives: A Sign of the Times

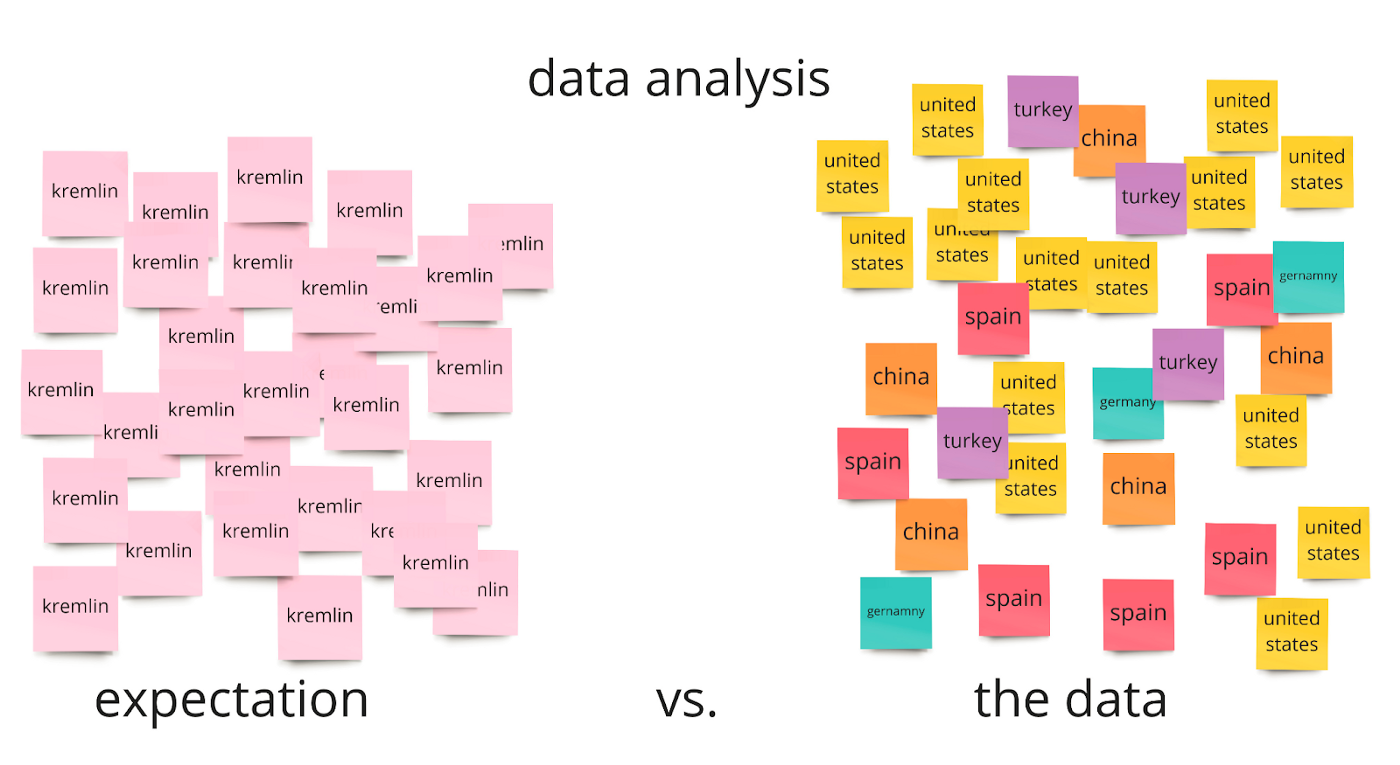

Using the open data set and reflections we experimented with different visualizations of our data. One initial observation was the difference between our data sources. While the report conducted by the EU mentioned the Kremlin 34 times and Russia 120 times, there was little to mention of Russia and the Kremlin from the data set from Princeton.

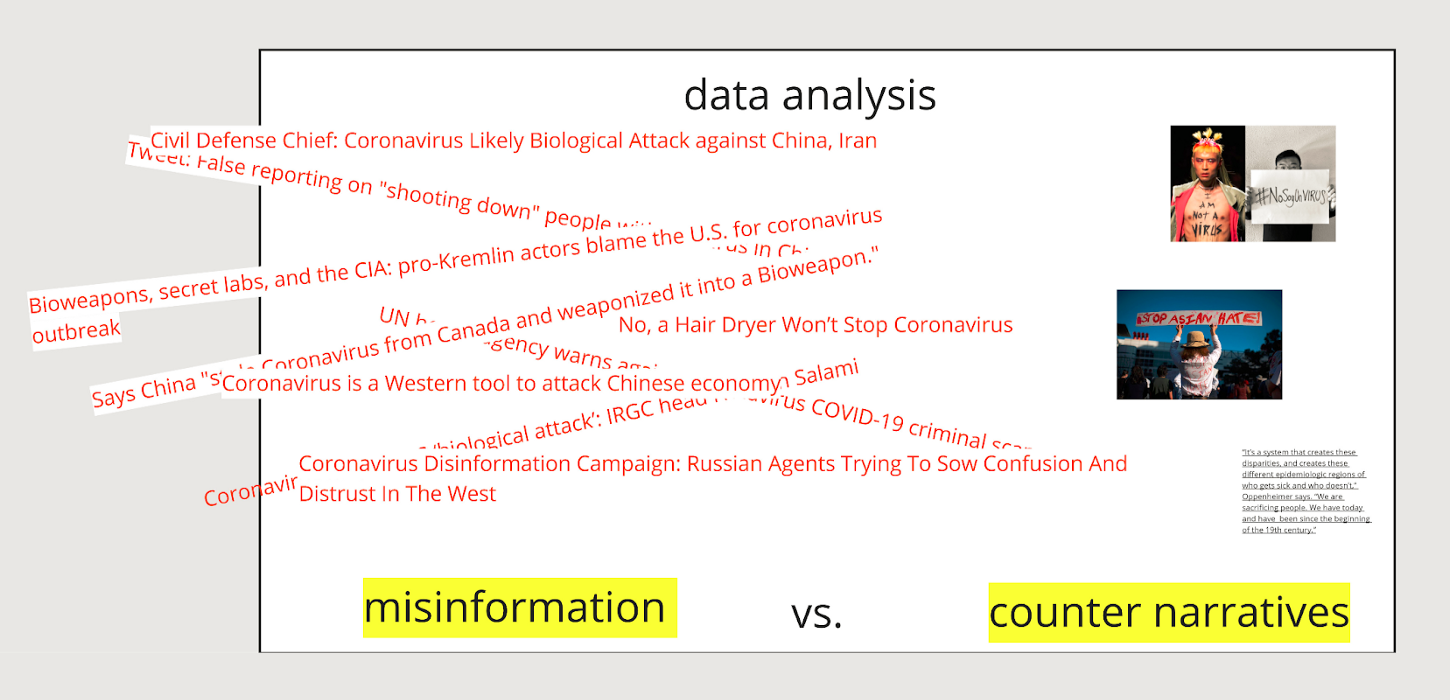

Additionally, the following visualization was a reflection finding a lot of examples of misinformation but fewer counter narratives.

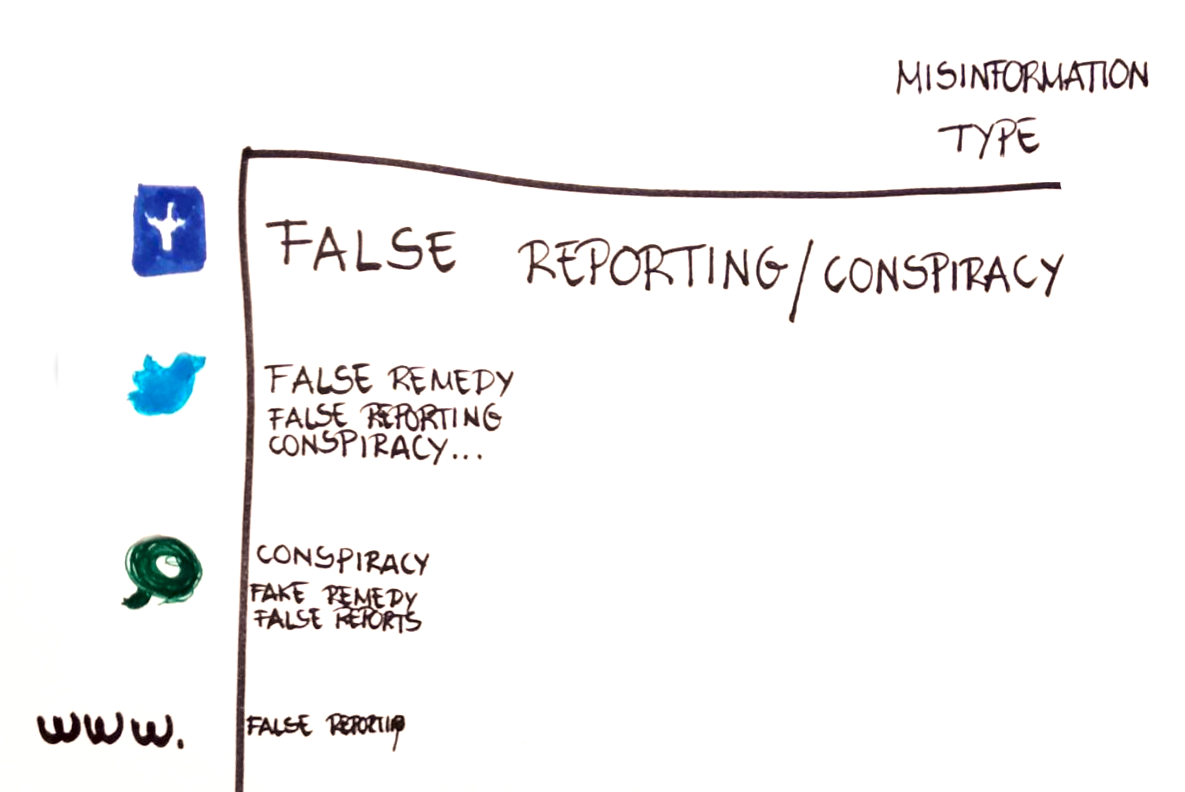

And the following visualization captures types of misinformation and medium they are most spread on:

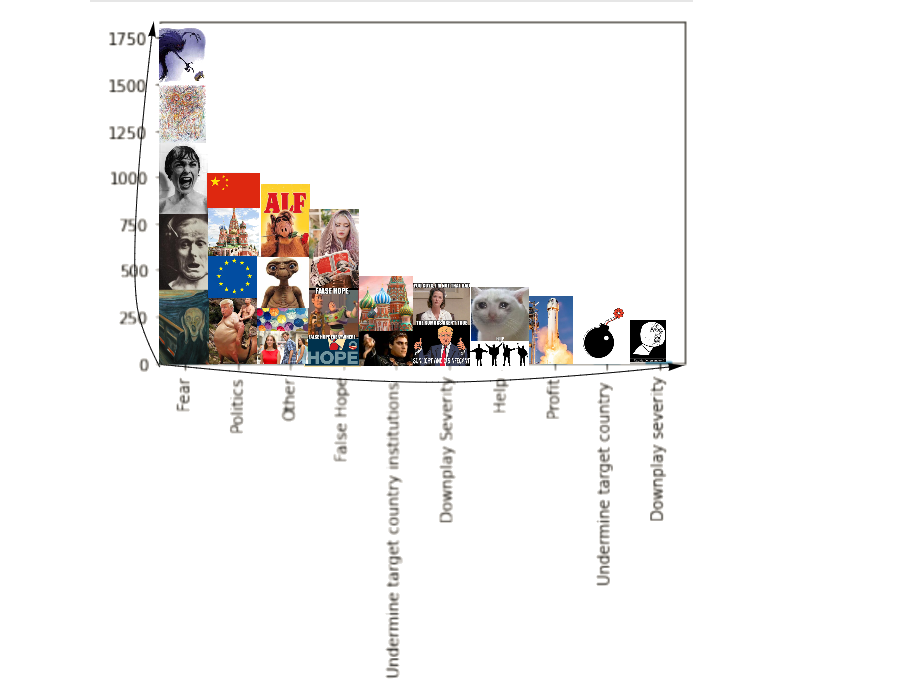

Creating visual narratives in a collaborative and playful manner, as we did, has brought us together for an insightful exploration resulting in a creative data visualisation of the main motivations that are behind the misinformation and hate speech.

Below is a graph of the reasons for creating hate speech which were then filled with images and memes that we thought captured each sentiment. The activity and visualization were interesting because essentially they are now artifacts that capture both data and images that capture what we’re feeling and how we are feeling them.

Motivations for Misinformation and Hate speech

cc-by-sa Platoniq

Conclusions

Ultimately our research reminded us of the collective role we all play in maintaining each other’s dignity and humanising each other in the face of disinformation and polarizing news. GLAMs such as museums and libraries can and have played a role in opening up spaces for visitors to observe and reflect on society’s issues and there is an ever present need for them to do so. Projects such as SMILEs (External link) are necessary for cultural heritage institutions when envisioning their future and their role in society to go beyond just being a respository of the past but also assume the role they play in society’s collective critical thinking. At this moment in time with changing notions of culture and cultural heritage, as collectors of histories GLAMs need to reckon with their responsibility and role of harmful colonial and nationalist narratives and re envision their future both on and offline. And perhaps it might even be helpful for people to be able to confront the pressing or polemic issues from the distance and doses of information offered in an exhibition.

Cultural institutions have the unique space of allowing for power to be contested and challenged; they also have the resources with artifacts to think about the past, and as such with the presence of dangerous misinformation these institutions should rise to the occasion of challenging the systems behind inequalities, adapting to new digital realities, and creating new uses with artifacts of the past to build more just futures.

The inDICEs Project

This article was originally published in the inDICEs Open Observatory. You can read the original post here.

inDICEs is a research project funded by the Horizon 2020 program in response to the new challenges that digitization and the Digital Single Market represent for European culture. The goal of inDICEs is to enable policy and decision-makers in the cultural heritage sector (GLAMs) to understand the social and economic impact of digitization on the cultural sector. The project also aims to address the need for innovative (re)use of cultural assets. In this regard, the InDICEs platform — the InDICEs Open Observatory — has emerged to provide tools and resources to cultural heritage sector decision-makers to better understand and strategize for the future around the digitization of culture.

References

- https://visualaids.org/artists/barton-lidice-bene (External link)

- https://citylimits.org/2020/08/17/cholera-yellow-fever-flu-pandemic-lessons-from-nycs-past/ (External link)