At (Co)incidim, we come together to make an impact. We bring together social movements, grassroots environmental groups and other strong-willed individuals who work tirelessly towards constructing a more open, just and caring society, both in how we relate to people and to the natural world.

By working together – through meetings, collaborations and bringing people together – we aim to make an impact on local, metropolitan and national policy because we believe that citizens have the right to express our opinions and participate in the management of public resources. Nevertheless, we are aware that in order to take part and make fully informed decisions we need to revindicate the right to information, to learn from and value collective wisdom, and to empower ourselves to build a critical citizenry capable of engaging in debate and decision-making to prioritise the common good over capital and individual greed. To achieve this, we find it imperative to adapt to modern times and promote innovative democratic systems through the introduction of digital tools. These tools will not substitute in-person processes, but rather complement them and expand their reach.

(Co)incidim is a digital tool for citizen empowerment which is still very much in its infancy. It is the result of symbiotic collaboration between Enginyeria Sense Fronteres (ESF, Catalan: Engineers Without Borders) and Platoniq, and was spearheaded by Barcelona Activa via the program “Impulsem el que fas” (Catalan: “We promote what you do”), as well as the digital citizen participation platform Decidim (Catalan for “We decide”), out of which (Co)incidim has grown.

Taking Back Control of Water and Energy

Since 1992, we at Enginyeria Sense Fronteres (ESF) have been carrying out projects on international cooperation, advocacy and raising awareness in the fields of water and energy. Our 28 years of experience have enabled us to construct critical discourse which focuses on creating a governance model for these resources. In order for water and energy companies to meet local needs and guarantee universal access, they need to be operated and managed in a way that involves citizens and communities, guarantees democratic integrity and acts in the interests of the common good.

In order for water and energy companies to meet local needs and guarantee universal access, they need to be operated and managed in a way that involves citizens and communities, guarantees democratic integrity and acts in the interests of the common good.

In our region, the fight for basic services has long been an uphill struggle. Despite the neoliberal assaults of the 1990s and the blatant failure of the privatised model promoted by international financial institutions, only 10% of the world’s population continues to receive its water supply from private companies, but in Catalonia this number stands at 80%. With regards to energy, control of the system remains in the hands of five large companies which, despite laws prohibiting such practices, control the generation, distribution and commercialisation of energy. These situations, in practice, create an energy market built on privilege and the imbalance of power, in which the management of water and energy is controlled by a cluster of large businesses, who answer only to commercial interests.

To confront this situation, social movements such as Aigua és Vida (Catalan: Water is Life), the Moviment per l’Aigua Pública i Democràtica a l’AMB (MAPiD, Catalan: Movement for Democratic Public Water in Barcelona) and the Aliança contra la Pobresa Energètica (APE, Catalan: Alliance against Energy Poverty) have been organised to fight injustice and guarantee the universal right to basic services. In this ongoing struggle, there are specific needs which must be met.

With regards to water, this service is handled by Aigües de Barcelona — a joint venture controlled by the Agbar group — which supplies 23 municipalities. The recent controversial Supreme Court ruling upholding the dubious legality of the company’s incorporation has halted imminent plans for remunicipalisation. Nevertheless, social movements continue to call for the creation of citizen watchdog organisations and the joint creation of public policies, but before any of this can happen we must guarantee the right to information, which is of the utmost importance for encouraging proper, effective civic participation. Faced with a secretive company completely lacking transparency and a weak and compromised administration, our challenge is an ambitious one: how can we organise the citizens of 23 municipalities spread out over an area of more than 600km²?

In terms of energy, one of the APE’s greatest successes was the passing of Catalan law 24/2015, which prohibits cutting off supply in situations of economic vulnerability, applying a precautionary approach in all such cases. In order to pass the law, various municipalities set up Energy Advice Points (Spanish acronym PAE) to assist citizens in guaranteeing access to energy supply. Even so, as a result of mala praxis by energy companies and general misinformation, it became necessary to firstly inform the public of the PAEs and related services, and secondly, to compile information on problems caused by energy poverty via crowdsourced data, such as supply cuts within the region.

The Creation of (Co)incidim

Faced with the aforementioned situation, and taking into account the impact of social networks on how we communicate, we have identified the need to map out new steps to be taken. This will be done by seeking out new methodologies which will allow us to build community spaces, harness collective intelligence, strengthen it through cooperation and togetherness and liberate it from the onslaught of cognitive capitalist platforms which aim to privatise knowledge and interaction in the service of a select few.

Open tools for citizens’ digital empowerment. Guaranteeing access to basic services.

cc-by-sa Platoniq

It was this perspective that led to the synergistic relationship between ESF and Platoniq – Creativity and Democracy respectively. Since 2005 the latter has been developing open source software and participatory methodologies to promote civic empowerment and participation. If the affinity of each organisation’s values was what brought them together, then their complementary aims and knowledge were the key to creating (Co)incidim: the in-person participation championed by ESF is enhanced and strengthened by the incorporation of the new technology and methodologies promoted by Platoniq. (Co)incidim is all about hybrid participation.

This hybridisation has been possible thanks to the adaptation of the digital civic participation platform Decidim. Our decision to use Decidim amounts to more than just taking the popular “open source” route, as it goes above and beyond in its ethical interpretation of software. This is as much in its development, distribution and commercialisation as in its shared values of collaboration, transparency, integrity, challenging discrimination and, above all, freedom. This is how working methods can inspire social movements when it comes to building community, as they can work towards both tangible and intangible aims.

This is how the (Co)incidim project came about, by creating a version of Decidim adapted to the needs of social movements fighting for the universal rights to water and energy access, placing people at the centre and making them the protagonists of the decision-making process.

Technical Elements of (Co)incidim

In (Co)incidim you will find two main participative processes: we are working on improving water management in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area, and on el Mapa de la Energía (The Energy Map). There are also various assemblies being organised, but these are private and are open only to members of the working team. (Interested in joining? Write to us at bcnaigua@gmail.com)

Available digital tools: Energy map (Interactive energy map that collects information of interest and issues arising from energy poverty and its management.) and Entities map (Map of the entities working for a new governance and management model for public services in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area.)

cc-by-sa Platoniq

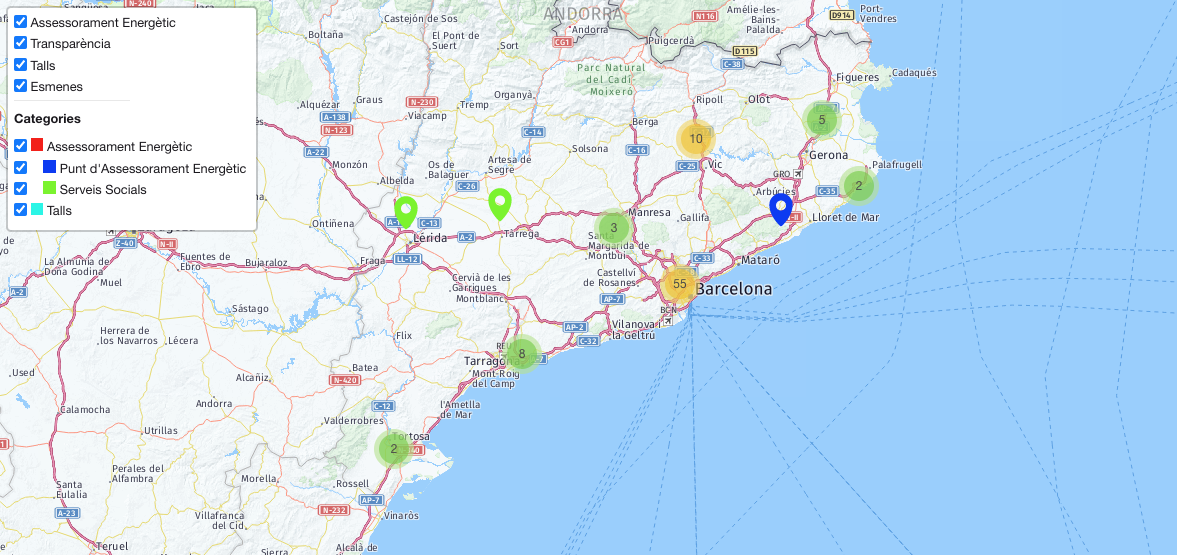

In technical terms, the platform’s most significant development is the “Awesome Map”. This feature, which can be used in any participative space, displays a full-screen map containing precise locations for all meetings and proposals published through a process or assembly. The points on the map are colour-coded according to category, and when clicked display more detailed information. In our case, we have compiled information from three “Proposals” components (energy advisory service, municipal transparency, and reported service cuts) to create The Energy Map. Aside from displaying the map itself, this feature allows for crowdsourcing information, as any user can create new points (proposals) on the map.

Other fundamental features for our processes and assemblies have been the questionnaire, through which we have been able to assess citizens’ priorities with regards to water supply in the metropolitan area; the webpage, where we publish questionnaire results; meetings, which have allowed us to centralise the content, minutes and commitments resulting from each meeting; participative texts, through which we can revise and review – both in person and remotely – water strategies; collaborative drafts, through which we collectively wrote the “Manifest per l’aigua a l’AMB” (Catalan: Barcelona Water Manifesto); tracking which allows us to receive updates on aspects of projects in progress such as objectives, actions and expected outcomes; and finally proposals, which in addition to their use in creating the map, have enabled a more general mapping of entities, proposals for actions to be taken or reporting technical errors on the platform.

Challenges and Future Outlook

The main challenges we face are the same as those that civic participation movements have already faced for a long time. On one hand there is the question of redistributing power, which must extend not only to the handling of basic services services. but to the entire democratic system in order to recognise the role and importance of everyday citizens. In this sense, and since the project seeks to achieve objectives which the administration is obligated to respect, we must ask how we can share the burden. This intersects with the structural challenge presented by the current model of how basic services are managed: how can we balance out power dynamics with the influence of certain actors?

Keeping in mind the aforementioned difficulties, our strategy is rooted in the collective knowledge of the general public, aiming to synthesise and coordinate numerous, already existing perspectives, and in so doing acknowledge the value of citizen empowerment. This philosophy is what lies behind the crowdsourcing of data via maps, and what we believe legitimises our demands for recognition, creation of spaces for citizens and the redistribution of power in our administrations.

In designing a hybrid platform such as (Co)incidim, we have to ask ourselves how we can connect in-person and digital processes. Perhaps even more importantly, we must ask how to avoid generating new forms of digital inequality in a project which aims to make access to participation a fundamental right.

In this project we have also confronted challenges with regard to the design of the Decidim platform. If we choose to adapt the platform to meet specific needs, as is the case with (Co)incidim, the possibilities of elements such as the “Proposals” feature must be explored, as it currently focuses heavily on claims against the administration. Small modifications, such as one-step addition of new proposals or finding ways to improve Decidim’s mobile user interface, could make civic participation easier.

Lastly, our wish is that (Co)incidim can inspire many more citizen-led projects, and contribute to the burgeoning support for questioning or breaking away from our current democratic system. The decision to implement new participatory tools and mechanisms is something which in itself pushes us towards a redistribution of power. Taking part in a project such as this means leaving an indelible footprint on the path towards building truly democratic societies for all.